Fictional Kazakhstan

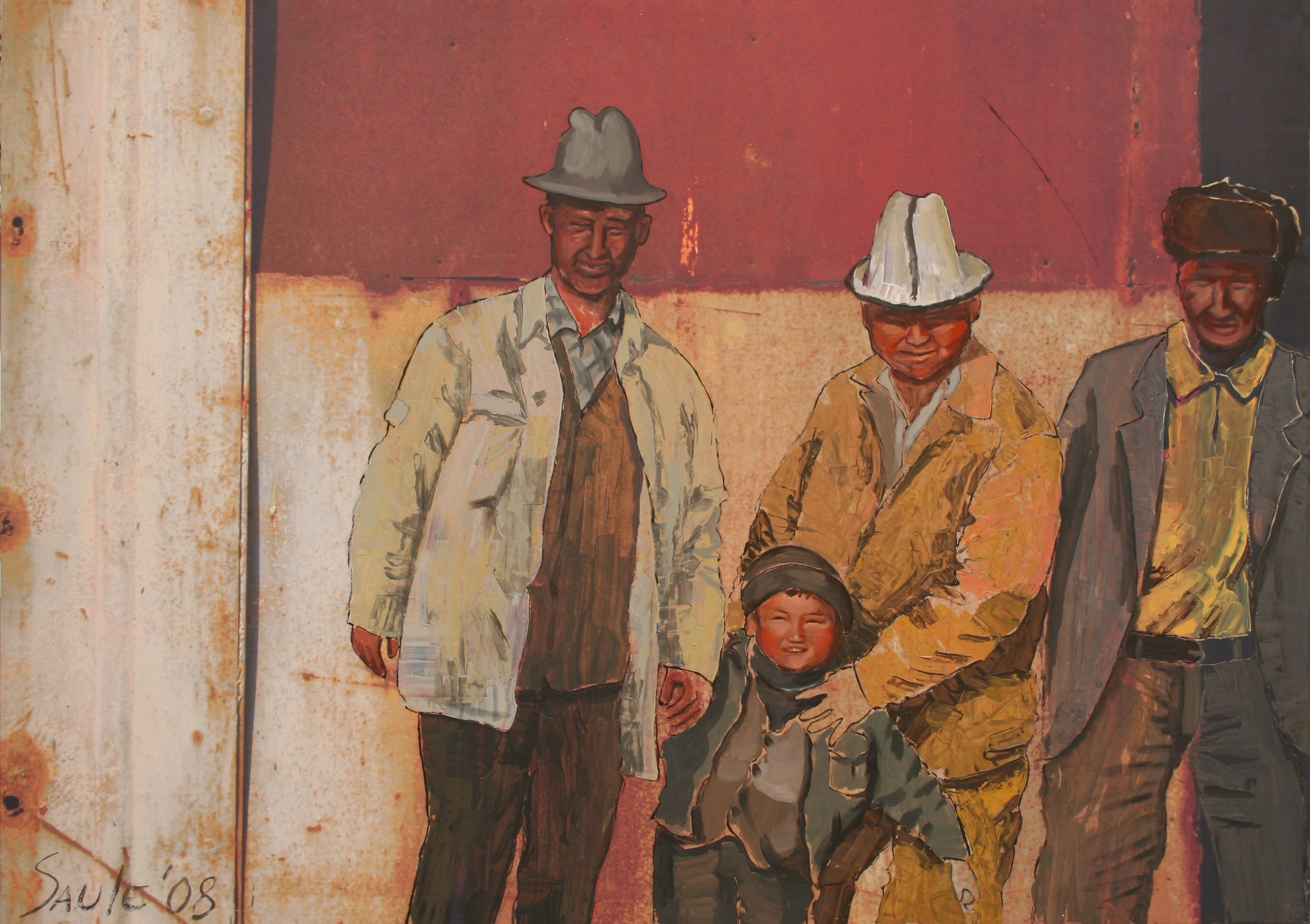

In 2010, Radio Azattyk released a short report on I’m Kazakh, an exhibition by artist Saule Suleimenova held in Almaty at the time. The exhibition was centred around paintings on photographs — portraits of Kazakh people against the background of garages and courtyards. The report was called nothing else but 'Borat Who Paints.’ It explained that some critics had given Suleimenova this moniker because, in their view, her work “portrays Kazakhs in an unflattering light.” The artist responded, “Art must be based on truth, which is so lacking in 1 Boltay, E. (2010, May 5). “Borat Who Paints” ["Borat, Kotoryi Risuyet"] [Video]. Radio Azattyk. https://rus.azattyq.org/a/2032730.html It is telling that, despite his various qualities – Borat, in this context, appears solely as a figure who tarnishes Kazakhstan’s reputation. Yet he remains a character from an imaginary country that shares a name with Kazakhstan but bears little resemblance to the real nation, even if similar surroundings might indeed be found there. While Borat thrives on misrepresenting Kazakhstan, Saule Suleimenova pursues the exact opposite, seeking out what she calls the 2 Verko, R. (2018, November 14). Saule Suleimenova: The Journey in Search of True Kazakhness [Saule Suleimenova: Put v poiskakh istinnoy kazakhskosti]. Central Asian Analytical Network. https://www.caa-network.org/archives/14552 This fifteen-year-old report, with its ambiguous title, still offers ample room for reflection — beyond simply questioning why Suleimenova was compared to Borat in the first place. In this essay, I would like to discuss what kinds of truth are lacking in Kazakhstan and how this is reflected in art; how Kazakhstan is imagined in politics and culture; and, in turn, how such fabrications shape reality.

The phenomenon of fiction presented and experienced as fact has been termed parafiction by art historian Carrie Lambert-Beatty. She uses this term to describe artworks that, through stylistic mimicry and performativity, create an effect of plausibility. In broader culture, parafiction is often associated with political satire, whereas outside the artistic context, it can take on a destructive 3 Lambert-Beatty, C. (2009). Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility. October, 129, 56. https://doi.org/10.1162/octo.2009.129.1.51 , bordering on deception, forgery, or fraud.

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2006, dir. Larry Charles) is a mockumentary about the journey of a Kazakhstani reporter through the United States. Borat's Kazakhstan – a poor, uncultured, uncivilised country – stands in stark contrast to the image that Kazakhstani politicians would like the young nation to project on the international stage. “What we are concerned about is that Kazakhstan – terra incognita for many in the West – is depicted in this 4 Myers, S. L. (2006, September 28). Kazakhs Shrug at ‘Borat’ While the State Fumes. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/28/movies/kazakhs-shrug-at-borat-while-the-state-fumes.html stated the spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Yerzhan Ashykbayev. In Kazakhstan, the film was not released, and Sacha Baron Cohen, who plays Borat, was threatened with legal action. Initially, politicians criticised the film and launched campaigns to expose its false portrayal of Kazakhstan. However, their strategy shifted when Baron Cohen began ridiculing their actions, and the focus on the film's credibility took a backseat. Some time after his critical article ‘Offensive and unfair, Borat's antics leave a nasty 5 Idrissov, E. (2006, October 4). Offensive and unfair, Borat’s antics leave a nasty aftertaste. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2006/oct/04/comment.television Kazakhstan's ambassador to the UK, Erlan Idrissov, concluded: “Let me admit it: we Kazakhs owe Sacha Baron Cohen, Borat’s creator, a debt… In a sense he has placed Kazakhstan on the 6 Idrissov, E. (2006, November 4). We survived Stalin and we can certainly overcome Borat’s slurs. The Times. https://www.thetimes.com/travel/destinations/europe-travel/we-survived-stalin-and-we-can-certainly-overcome-borats-slurs-bbvzzlwtclb?region=global However, the influx of tourists, which politicians used to defend Borat, negatively impacted the country's 7 Pratt, S. (2014). The Borat Effect: Film-Induced Tourism Gone Wrong. Tourism Economics, 21(5), 977–993. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2014.0394 while the film fueled ethnic prejudice 8 Kelleher, E. (2020, October 27). Kazakhstan: Racism Disguised as Satiric Humor Is No Laughing Matter. Asia Media International. https://asiamedia.lmu.edu/2020/10/27/kazakhstan-racism-disguised-as-satiric-humor-is-no-laughing-matter/ In 2020, with the release of the more politically-charged Borat sequel, Kazakh Tourism launched the Kazakhstan. Very Nice! PR campaign. Their promotional videos advertise Kazakhstan as a developed, cultured, rich, prosperous, and friendly country, where mesmerized foreign tourists repeat Borat's signature phrase, giving it a positive connotation.

In Kazakhstan, as in many other countries, politicians often invent and promote a version of events they deem favourable. Propaganda parafictions are used to create and maintain the image of a ‘modern progressive 9 President's Address: “Growing Welfare of Kazakh Citizens: Increase in Income and Quality of Life.” (2018, October 5). Official Information Source of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Kazakhstan. https://primeminister.kz/en/address/05102018 both domestically and abroad. There are many examples — Kazakhstan is constantly being reinvented. Thus, in 2016 we celebrated the 10 Uatkhanov, Y. (2016, September 21). Almaty celebrates 1,000th birthday. The Astana Times. https://astanatimes.com/2016/09/almaty-celebrates-1000th-birthday/ of the city of Almaty; in 2022 we experienced an attack by 20,000 11 Tokayev, K.-J. (2022, January 7). President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s Address to the People of Kazakhstan. Official Website of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan. https://www.akorda.kz/en/president-kassym-jomart-tokayevs-address-to-the-people-of-kazakhstan-801221 and finally, in 2024 we learned about the absence of political persecution and 12 President of the Republic of Kazakhstan Kassym-Jomart Tokayev: As a progressive nation, we must look only forward! (2024, January 3). Baiterek National Managing Holding. https://baiterek.gov.kz/en/pr/news/president-of-the-republic-of-kazakhstan-kassym-jomart-tokayev-as-a-progressive-nation-we-must-look-o Since the latter claim is false, the government continues irresponsibly to produce such fabrications. It is precisely such fables that have been ridiculed by Qaznews24, a satirical news agency, since 2021. Their humorous news reports, styled like real ones on social media, at times gain credibility despite disclaimers about their fictional nature."The Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kazakhstan has proposed granting Nursultan Nazarbayev the status of a god and enshrining it in the constitution," reads the headline of one of Qaznews24's most popular posts. This was a satirical reference to his status as ‘Elbasy,’ or leader of the 13 However, the law regarding ‘Elbasy’ was later repealed, and references to the first president were entirely removed from the Constitution. The clergy issued a formal rebuttal, urging the public not to believe fake news. From the launch of Qaznews24, its creator, Temirlan Yensebek, faced threats and surveillance; his apartment had been searched. Eventually, a case was opened against him for spreading false information. Despite gaining a significant following, the agency was temporarily suspended, and its social media accounts were shut down. The case sparked public outcry, and a year later, Yensebek relaunched Qaznews24, which continues its work to this 14 At the time of this essay’s publication, Temirlan Yensebek is once again facing criminal charges for ‘inciting ethnic hatred’ for the Instagram post of Qaznews24. The author joins calls for his release and for the cessation of unlawful prosecution. highlighting the incompetence, bias, and stupidity of political and public figures and focusing on relevant issues. Occasionally, it offers imagining positive news that local authorities, for example, support and protect LGBTQ+ 15 Qaznews24 [@qaznews24]. (2024, March 7). On March 7, a rally for LGBTQ+ rights was held at Gandhi Park [7 marta v parke Gandi proshel miting za prava LGBTK+ soobshchestva] [Post]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/C4NSzp5NlBe/

The main reason many people believe Qaznews24's satirical news is real is its resemblance to local news, particularly that of pro-government media. The absurdities of state-run news channels, the conformity of their staff, and the persecution of young female activists are explored in Assel Aushakimova's 2024 film Bikechess. In Kazakhstani cinema, the country is depicted in various ways, including semi-fictitiously. However, the director of Bikechess bases the plot on real reports, emphasizing their constructed nature through artistic narration. It's the inverse of Borat — here, the real Kazakhstani journalism is disguised as fiction. The film’s title and opening scene, for example, were inspired by a press release that doesn’t quite pass the fact-checking test: ‘A New Sport Has Been Invented in Kazakhstan – Bikechess: Chess Players Pedal During the 16 A New Sport Created in Kazakhstan – Bikechess: Chess Players Pedal During the Game. [V Kazakhstane pridumali novyy vid sporta – veloshakh: shakhmatisty krutyat pedali vo vremya partii]. (2019, April 19). Informburo.kz. https://informburo.kz/novosti/v-kazahstane-pridumali-novyy-vid-sporta-veloshah-shahmatisty-krutyat-pedali-vo-vremya-partii.html Aushakimova critiques the tendency of propagandists to attribute various achievements to the state, no matter whether they are true. In another scene of Bikechess, a pseudo-scientific book presentation is featured, claiming to prove that life on Earth originated on the territory of Kazakhstan. This mirrors an actual 17 Mangiatordi, L. (2020, March 4). Life on Earth Originated in the Steppes of Turan, Says Kazakh Scientist (Video) [Zhizn' na Zemle voznikla v stepi Turan, zayavil kazakhstanskiy uchenyy (Video)]. NUR.KZ. https://www.nur.kz/society/1843860-zizn-na-zemle-voznikla-v-stepi-turan-zaavil-kazahstanskij-ucenyj-video/ by Rakhman Alshanov, author of Secrets of the Twenty Millennia: Searches and Discoveries (2020), an economist, deputy, and rector of Turan University.

Pseudo-historical national myths have accompanied Kazakhstan since its independence. Following authors like Kalibek Daniyarov, who rewrote history and, among other things, claimed Genghis Khan was Kazakh, artist Kuanysh Bazargali created an alternative history of Kazakhstan’s future. In his 2013 project When All People Were Kazakh, he imagined Kazakhstan becoming the world’s superpower after a comet struck and a global flood occurred. To maintain its status, the state falsified world history, including cultural heritage, by placing Kazakhs at the center of all historical events. “Legends spread across the country about a great Kazakh general, Iskander Make Dona, who enslaved wild European tribes and expanded the boundaries of the Kazakh khanate. Elders told stories of their great ancestors and a terrible world war, where Kazakh aviation destroyed Pearl Harbor, and then bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and how General Zhukobaev led the Kazakh army into Berlin (somewhere in Europe), with two Kazakh soldiers, Bulatov and Koshkarbaev, hoisting the blue victory flag over the Reichstag (the ancient 18 Bazargali, K. (813 years after the G.F.). When All the People Were Qazaqs [Kogda vse lyudi byli kazakhskimi]. Kuanysh Bazargaliyev. http://kubazargaliyev.tilda.ws/whenallthepeoplewereqazaq Bazargali also created a series of paintings that he presented as restored ‘lost masterpieces of world painting, but not in their original form, rather in accordance with the state's ideological 19 Bazargali, K. (813 years after the G.F.). When All the People Were Qazaqs [Kogda vse lyudi byli kazakhskimi]. Kuanysh Bazargaliyev. http://kubazargaliyev.tilda.ws/whenallthepeoplewereqazaq

In his work, Kuanysh Bazargali mentions the renowned Kazakh thinker and artist Serik Maslanov, author of When Kazakhs Were Cosmonauts . According to Bazargali, Maslanov's research suggests that ‘Kazakhs arrived on Earth via a meteorite, thus confirming the divine purpose of this 20 Bazargali, K. (813 years after the G.F.). When All the People Were Qazaqs [Kogda vse lyudi byli kazakhskimi]. Kuanysh Bazargaliyev. http://kubazargaliyev.tilda.ws/whenallthepeoplewereqazaq The reference is to Sergey Maslov, a pioneering figure in Kazakhstan’s contemporary art scene, who claimed that ‘Kazakh people came from Sirius and are direct descendants of 21 Evdokimenko, K. (2012, April 26). Here Was Maslov [Zdes byl Maslov]. Vremya. https://time.kz/news/archive/2012/04/26/zdes-byl-maslov Maslov was known as a mythmaker who played with the trust of his audience through mystifications, including about himself. In 1999, he dedicated several works to American singer and actress Whitney Houston, claiming that they had engaged in a romantic correspondence. To prolong her life, he once allegedly took his own life — a fabricated story many believed, thanks to an obituary posted at the Voyager gallery in 22 Evdokimenko, K. (2012, April 26). Here Was Maslov [Zdes byl Maslov]. Vremya. https://time.kz/news/archive/2012/04/26/zdes-byl-maslov

“I had never even heard of such a country as Kazakhstan before. I searched for a translator to translate a letter from Kazakh, but then it turned out that the letter was written in 23 Maslov, S. (1999). From correspondence with Whitney Houston [Iz perepiski s Uitni Khyuston]. Almanach “Tamyr”, 1-2, 114-115. https://refdb.ru/look/2442018-pall.html says a letter from Houston, where Maslov projects a relatively realistic view of the new (fictional?) post-Soviet state from abroad. He satirises the contrast between the fame of her persona and that of an entire country, as well as the scale of Western pop culture versus the local one: “I heard that many festivals and competitions are held in your country. Could you help me get into the program for 'Asia Dausy' or 'Season of the East'? Yours forever, 24 Maslov, S. (1999). From correspondence with Whitney Houston [Iz perepiski s Uitni Khyuston]. Almanach “Tamyr”, 1-2, 114-115. https://refdb.ru/look/2442018-pall.html It’s unclear which is easier to believe: Maslov’s grandiose stories about the Kazakhs or his romance with a global pop star. Either way, these myths are linked to the reflection on Kazakhstan’s independence and its ironic representation in politics, culture, and society.

A different approach to self-mythologization can be observed in the work of Almaty-based artist Katya Nikonorova. In 2014, she proclaimed herself the reincarnation of the Central Asian goddess Katipa Apai, around whom the mythology of Katipaapism developed. Katipaapism is described as a ‘branch of the white cult of the goddess Umai in modern Tengriism.’ Dressed in a white dress and kimeshek, Katipa Apai conducts neo-shamanic rituals — ranging from the ‘sanctification of Almaty’ to ‘healing the nation’ — transforming every space into her Temple of Arts, a ‘neo-nomadic para-institution.’ Its imaginary and wandering nature reflects both the idea of neo-nomadism and the reality where Central Asian artists create fictional structures to ensure that ‘the temple doesn't 25 Храм Искусств Катипы Апай / Katipa Apai Temple of Arts. (2019, October 25). KATIPAAPISM: A Methodological Guide to the Modernization of Consciousness [KATIPAAPISM: Metodicheskoe Posobie po Modernizatsii Soznaniya] [Post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/story.php/?story_fbid=1828178773980858&id=422109247921158&_rdr

Back in 2012, Maria Vilkovisky and Ruthia Jenrbekova founded a fictional cultural centre, a paranormal institution (parastitution) called the Krёlex zentre. Representing translocal queer people of mixed heritage, they organise exhibitions, actions, and other public events, perform poetry and performances, and produce publications. “Designing paper organisations, as well as situations and connections, is our version of the constructivists’ abstract compositions. In practical terms, the creation of imaginary institutions is a necessity in countries with acute institutional deficiencies, as it is the only way to generate the cultural context without which an 'artistic situation' cannot 26 Krёlex zentre. (2021). Artistic democracy and its fake institutions [Khudozhestvennaya demokratiya i yeyo nenastoyashchiye instituty]. Horizon. https://horizon.tselinny.org/ru/issues/1/kreolex-center Both para-institutions use the fictional form as an artistic method, infusing their fictive self-organisations with cultural context.

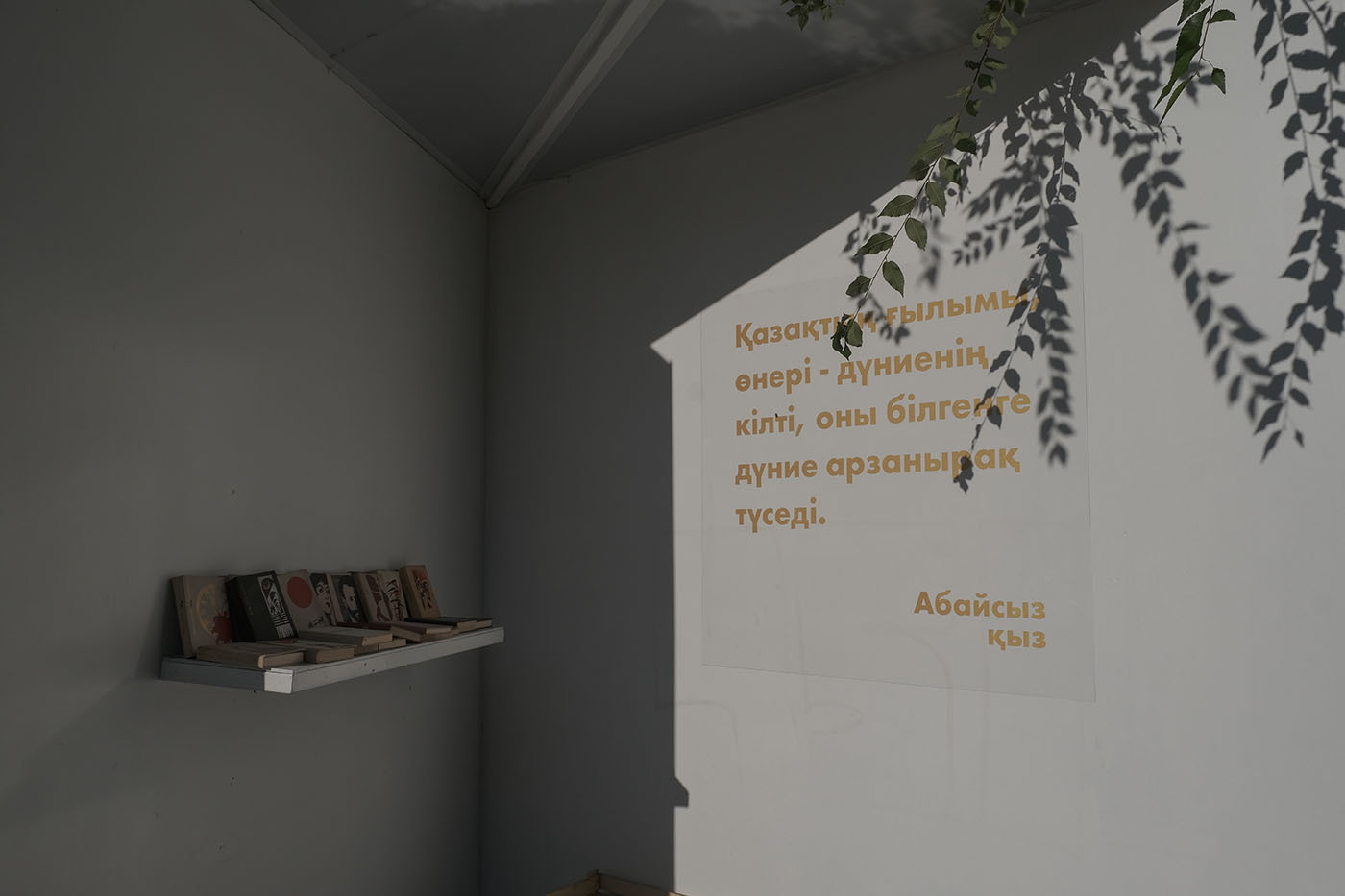

In a sense, with the aim of ‘healing the nation,’ parafiction can become a decolonial tool. In her project Abaisyz Qyz (Aбайсыз қыз, 2023), artist Dariya Temirkhan selected two quotes from The Book of Words by Abai, replacing the word ‘Russian’ (орыс) with ‘Kazakh’ (қазақ), and displayed them in a public space near the National Library as authentic statements by the poet. “One should learn to read and write Kazakh. The Kazakh language is a key to spiritual riches and knowledge, the arts and many other treasures... Kazakh science and culture is a key to understanding the world, and having got it, we can actually make life easier for our 27 The original quote from Abai Kunanbayev's The Book of Words reads: “One should learn to read and write Russian. The Russian language is a key to spiritual riches and knowledge, the arts and many other treasures... Russian science and culture is a key to understanding the world, and having got it, we can actually make life easier for our people.” With this gesture, Temirkhan demonstrates how parafiction, like state propaganda, can subtly intervene in everyday life.

From the homeland of Borat to a great power, from the birthplace of life on Earth to a country where authorities defend LGBTQ+ rights, the image of Kazakhstan in politics, culture, and art varies. These parafictions don't just create alternative narratives; they reflect and influence reality. The limited perceptions of Kazakhstan and the rise in national consciousness have given birth to various myths, including those about ‘true Kazakhness,’ as the search for truth requires multiple voices, perspectives, and interpretations. Art plays a key role in creating spaces where reality, fiction, and myth intertwine, forming a foundation for understanding a complex, layered present. From satirical news to fictional cultural institutions, parafiction becomes not only a form of critique but also an act of resistance. While the government distorts facts, manipulates information and punishes those who openly criticise it, artists find in parafiction a space for satire, exposing propaganda, rethinking history, and collective dreaming.