Storytelling the Bombs: Nuclear literatures in Kazakhstan and Mā’ohi Nui

On 4 November 1959, Jules Moch, the French delegate to the United Nations Committee on Disarmament and International Security, gave a speech at the UN headquarters in New York, in which he proposed to bomb Algeria. Moch was advocating for the testing of French nuclear weapons in the Sahara desert, which, he claimed, “created no danger” for anyone. In response to concerns voiced by the Moroccan delegate, Ahmed Taibi Benhima, Moch argued that the fears of those representatives “who showed particular alarm” – which Moch called “hearsay” and “objections of an emotional nature,” in contrast to his own “serious, objective, scientific manner” – were “unjustified.” “The ‘undeniable danger’ to which the Moroccan representative had just referred,” he continued, 1 United Nations, ‘Summary record of the 1043rd meeting: 1st Committee,’ held at Headquarters, New York, Wednesday, 4 November 1959, General Assembly, 14th session. United Nations Digital Library, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/858878?v=pdf.

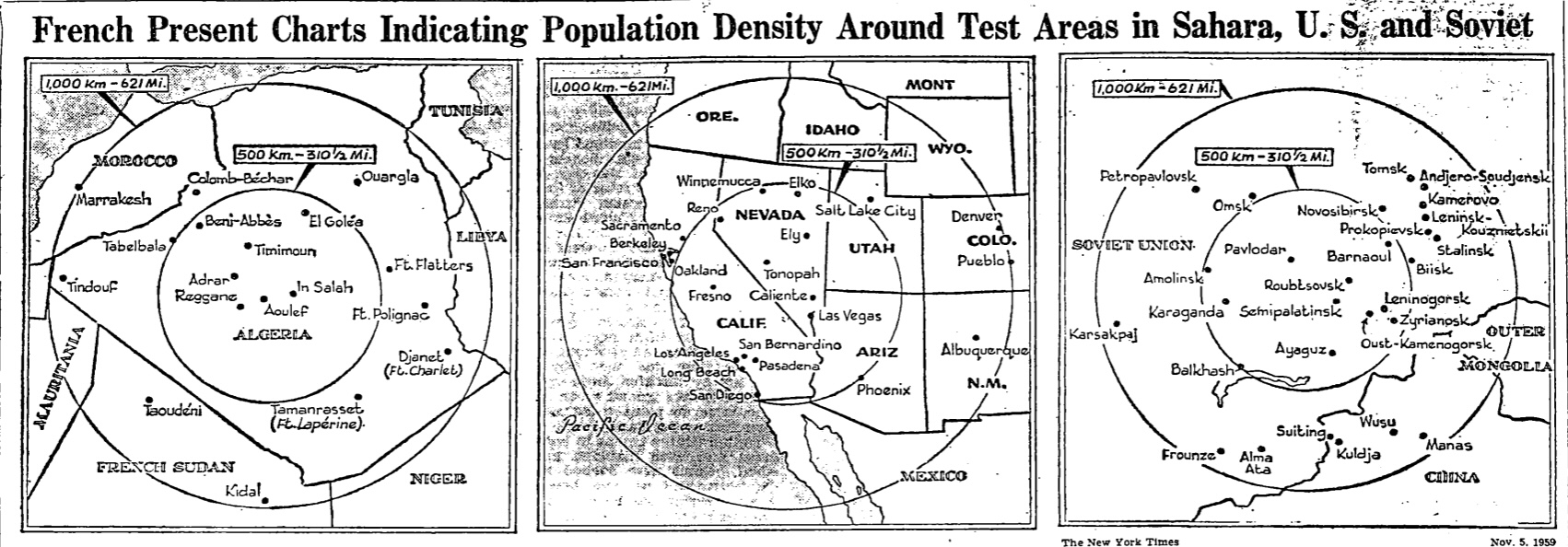

Moch’s presentation to the committee was accompanied by three maps (Figure 1), only one of which depicted the proposed location of the French bombings, in the Tanezrouft region of the Sahara 2 ‘Excerpts From Speeches By Delegates on French and Sahara Tests,’ The New York Times, November 5, 1959. See also, Jill Jarvis, ‘Radiant Matter: Technologies of Light and the Long Shadow of French Nuclear Imperialism in the Algerian Sahara,’ Representations, 1 November 2022; 160 (1), 78-79. . The other two, of Nevada and Semipalatinsk, served comparative purposes: the French tests, Moch went on to argue, would take place in areas far more removed from population centres than those other deserts and plains where the US and Soviet governments detonated their bombs, and would furthermore have a “virtually negligible” effect on the global levels of radioactivity, given the massive amounts already released by the nuclear testing programmes of 3 United Nations, ‘Summary record of the 1043rd meeting.’ .

It is perhaps understandable that France would seek discursive kinship with the US, a historical ally whose scientific and technological developments spurred many of France’s models for its own ‘radiant’ 4 Gabrielle Hecht, The Radiance of France: Nuclear Power and National Identity after World War II, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009), 1-2. . Potentially more surprising, though, is Moch’s reference to the Soviet Union, whose government was by then openly critical of French colonial rule in Algeria, and whose nuclear weapons were developed as part of a communist modern project, allegedly diametrically opposed to France’s capitalist one. Moch’s three maps instead invoked a new kind of transnational community of global superpowers, bound not by allegiance to a particular economic system or internationalist worldview, but rather by a shared project of developing nuclear bombs, which would, as a necessary consequence, be detonated in the deserts and borderlands of current or former imperial peripheries. In other words, Moch understood his country as seeking membership in a kind of transnational regime of 5 My use of “nuclear imperialism” is informed by Jarvis, “Radiant Matter,” 58. . 6 United Nations, “Summary record of the 1043rd meeting.” The UK, which had a much smaller nuclear weapons operation, detonated its first bomb in 1952, in Australia.

France began its bombing of Algeria only a few months later, in February of 1960, near Reggane, before moving its operations to In Ekker two years later, and then to Mā’ohi Nui (also known as French Polynesia) four years after that, in 1966. By then, the Soviet and American governments had already been conducting above- and below-ground nuclear tests for approximately two decades: the first US bomb, ‘Trinity,’ was detonated in 1945, in Nevada; the first Soviet bomb, Pervaiia Molnia, or ‘First Lightning,’ was detonated in Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan four years later. Nuclear testing would continue at all three sites until well into the 1980s and 90s; the French site on the Polynesian atoll of Fangataufa, where below-ground bombs were detonated as late as 1996, would be the last to close.

These individual state projects of nuclear bombings – and their devastating effects on indigenous lives and livelihoods – have been relatively well-studied. But there remains much to be gained by understanding these bombings, which occurred thousands of miles apart, as part of a shared project. Despite the nationalist rhetoric surrounding nuclear weapons manufacturing and testing in various states, the project of developing and detonating nuclear bombs was, in practice, collaborative and transnational, and the state architects of these projects relied on each other not only discursively, as Moch’s speech suggests, but also, in some cases, materially: some French researchers, for example, worked on the Manhattan project, the United States’ atomic bomb programme, and international conferences facilitated some exchange of 7 Hecht, The Radiance of France, 1-3. .

But if the bombings themselves belonged to a shared, transnational project of nuclear imperialism, might we then understand indigenous responses to them similarly transnationally? Recently, much excellent and necessary scholarship has examined not only local activism and resistance to the French, Soviet, and American bombings of their various peripheries, but also indigenous literary and artistic reckonings with them. What happens when we read these works in conversation with each other, as emerging from and reckoning with a shared experience of nuclear imperialism and its legacy? What can their shared motifs and preoccupations teach us about nuclear imperialism as a transnational enterprise?

Chantal Spitz’s 1991 novel L’île des rêves écrasés (The Island of Shattered Dreams) and Hamid Ismailov’s 2011 novella 8 (also titled Vunderkind Erzhan). both narrativise nuclear testing projects in Mā’ohi Nui and Semipalatinsk respectively. The two works tell similar stories about both the violence of the bombings themselves and the nationalistic (that is, French and Soviet) rhetoric of progress that accompanied them—as one character says in The Dead Lake, 9 “Мы не только догоним, но и обгоним американцев!” Hamid Ismailov, Vunderkind Erzhan, Druzhba narodov 9 (2011), https://magazines.gorky.media/druzhba/2011/9/vunderkind-erzhan.html. All translations mine. In The Island of Shattered Dreams, a French scientist observes, looking at photographs of the land razed to build a French nuclear weapons facility, 10 “Ce sont les témoins flagrants de ce progrès, ceux qui déposeront en faveur de la grandeur de notre pays.” Chantal Spitz, L’île des rêves écrasés (Pirae: Au vent des îles, 2007 [Kindle Edition]), 124. All translations mine. Both texts, in other words, capture a shared historical experience of twentieth-century state progress as both explicitly transnational and contingent on nuclear violence. But both texts are also similarly attentive to the act of writing itself, a preoccupation which is particularly revealing about the experience of nuclear imperialism and its aftermath.

We might understand these authors’ interests in the acts of writing and storytelling as, in part, an inevitable consequence of their subject matter. The violence of nuclear testing is, by nature, difficult to depict, and though individual bombs often occupy rarified spaces in popular culture (as exemplified most recently by the 2023 film Oppenheimer, about the 1945 Trinity test), ‘nuclear testing’ as a decades-long state project – and the bureaucratic and administrative apparatuses that accompany and constitute it – lacks the spectacular nature of a single, bounded event. The effects of these repeated nuclear bombings, moreover, are often impossible to perceive directly: though radioactivity is measurable, it is undetectable by human senses without the aid of special instruments. Insofar as the bodily effects of radiation exposure can be observed and felt, they often appear slowly, over the course of years, if not generations, and often require appeals to scientific or medical experts in order to be understood as ‘radioactive’ at all. To borrow Rob Nixon's well-known term for long-term environmental destruction in the Global South, 11 See also: Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011). .

The concerns of Spitz and Ismailov, then, are on the one hand related to the questions facing all authors of environmental literature: what might a literature of slow violence look like? How might one narrativise an almost invisible, years-long process of environmental and bodily devastation, and do so compellingly? But rather than answer these questions, both Spitz and Ismailov instead problematise the project of compellingly representing nuclear violence at all. Examined together, The Dead Lake and The Island of Shattered Dreams testify to anxieties about the written record that nuclear imperialism, as a transnational project, forces into being.

The story ofThe Dead Lake, we are told, begins ‘entirely prosaically’: a man on a train encounters a mysterious stranger, a twenty-seven year old man with the ‘unspoilt’ face and body of a child less than half his age. The Dead Lake unfolds as this stranger, Yerzhan, tells his life story: we learn about his first love, his talent for the violin, his miraculous acquisition of the Russian language, and his fateful encounter with the titular ‘dead lake,’ whose eerily still irradiated waters permanently freeze his appearance and height.

Hamid Ismailov’s 2011 novella is in many ways a direct commentary on the legacy of the nuclear testing conducted at the Semipalatinsk Test Site (also known as the Semipalatinsk Polygon). As the epigraph lays out in sterile, journalistic prose, the over 450 tests conducted between 1949 and 1989 released a lethal amount of radiation into the populated surrounding area. The combined explosive forces of these tests, measured in megatons, exceeded that of the American bombing of Hiroshima by a factor of a thousand. If Ismailov’s work marks an attempt to capture the ‘slow violence’ of the Semipalatinsk nuclear tests, Yerzhan serves as a concrete, visual representation of environmental devastation, the enormous scale of which otherwise defies narrative entirely. As the narrator concludes, we are meant to see in Yerzhan’s disabled body ‘time, an entire era of it, [that] had congealed in him, to be related… in a single gulp.’

But The Dead Lake also devotes considerable attention to its own narrative structure. Even as the novella is clearly concerned with the nature of the ‘slow violence’ of the Semipalatinsk nuclear tests, it is also remarkably sensitive to the particular way in which this slow violence is captured and retold: Yerzhan’s story, the narrative core of the book, occurs entirely within the frame of the narrator’s train journey through Kazakhstan, itself presented first as the recollection of events that happened ‘a long time ago,’ and, eventually, as a kind of fiction. By the story’s conclusion, the narrator’s account and the story he purports to tell come into explicit conflict: the former doesn’t facilitate the latter, but rather contradicts it, eventually replacing it altogether as a more compelling and palatable story of the narrator’s own making.

In forcing the reader to contend with the narrator’s unreliability, The Dead Lake not only undermines the narrator’s ultimate conclusions, but also confronts and problematises the very project of compelling representation of the violence of nuclear testing. What is lost, the novella seems to ask, when this radiant slow violence is sanitised? When the narrator first encounters Yerzhan on the train, he finds Yerzhan’s story of nuclear violence quite boring. Early on in the novella, the narrator says:

All steppe roads, including railroads, are long and monotonous, and one can shorten them only with conversation. Yerzhan’s story ran on and on, like the wires outside the window—from post to post, from post to post—and it seemed as though the clatter of the wheels lent his story beat after beat, beat after beat…

[His uncle] worked somewhere in the steppe, but more about that later. And more, later, about the television, that miraculous thing his uncle had once brought back from the city, for the sake of which Yerzhan would run to his uncle’s house.

12 ‘Степные дороги — будь они даже железные — долги, однообразны, и коротать их приходится лишь разговором. Рассказ Ержана тек, как провода в окне поезда — от столба к столбу, от столба к столбу, и, казалось, стук колес придавал его рассказу такт за тактом, такт за тактом… Ho об этом речь впереди. Как впереди речь о телевизоре, ради которого Ержан бегал опять же к Шакену-коке, после того, как тот однажды привез из города это чудо, поглотившее их с тех пор навсегда. А до того… До того…’ (Ismailov, Vunderkind Erzhan).

The narrator represents Yerzhan’s story in the language of steppe infrastructure: Yerzhan’s story is as linear as the cables outside the train (which run ‘from post to post, from post to post’), and as repetitive as the rhythmic turning of the train wheels (‘beat after beat, beat after beat’). This description represents a distinct value judgment: the narrator’s account of Yerzhan’s story endows it with the inevitable, ‘monotonous’ qualities attributed to ‘all steppe roads.’[1] This comparison is made yet more explicit early in the following chapter: as Yerzhan’s story continues, the narrator adds, ‘ 13 ‘Поезд ехал по степи, как рассказ Ержана–не останавливаясь. Не запинаясь, вперед и вперед’ (Ismailov, Vunderkind Erzhan).

If Yerzhan’s story represents an attempt to narrativise slow violence, then, for the narrator, it is an unsuccessful one: Yerzhan’s tale is ‘monotonous’ rather than compelling, and far less capable of entertaining him than is ‘conversation’—a two-person endeavour involving the interventions of an interlocutor. The narrator thus begins to rearrange Yerzhan’s story as he sees fit, forgoing its rhythmic linearity (‘from post to post,’ ‘beat after beat,’ ‘forward and forward’) for a kind of ham-fisted foreshadowing (‘but more about that later;’ ‘but before that… before that…’).

Later, however, The Dead Lake takes a strange turn: Yerzhan falls asleep, but his story continues, as the narrator, by his own admission, invents the next few years of Yerzhan’s life:

The daytime steppe, with its infinite posts, spread out before my eyes like a kind of endless music, with its own notes and rhythmic beats. But I couldn’t make out its meaning at all.

I tried to imagine how this story might end, keeping the corner of my eye on the upper bunk, where the twenty-seven year-old boy lay curled up in a tight ball… So what had taken place in the time between it happening and the present day – or rather, night – in which I simply couldn’t get to sleep?

Just as the lines of our train had been drawn along the steppe, I tried to sketch out the line between 14 ‘Дневная степь с бесконечными столбами вставала перед моими глазами, как какая-то бесконечная музыка, с нотами, тактами, но смысла ее я никак не мог разобрать. Чем же кончилась эта история, пытался я вообразить, глядя краешком глаза на верхнюю полку, где, свернувшись калачиком, лежал тертый жизнью мальчишка…Так что же произошло между тем, как случилось то и сегодняшним днем, а вернее, ночью, в которой я никак не мог уснуть? Подобно тому, как чертилась линия нашего поезда по степи, я пытался расчертить линию между тем, что я услышал, и тем, чего я не знаю’ (Ismailov, Vunderkind Erzhan).

As before, the narrator’s interventions serve not only to add narrative content (to fill the lacuna ‘between what I heard and what I didn’t know’), but also to disrupt the perceived monotony of Yerzhan’s story, which the narrator again compares to the endlessness of the steppe, with its ‘infinite posts,’ repetitive, regular ‘beats,’ and inscrutable ‘meaning.’ Accordingly, the narrator’s ‘invented’ account of Yerzhan’s life follows a recognisable narrative logic, and concludes with a clearly discernible ‘meaning.’ While Yerzhan sleeps on the bunk across from him, the narrator invents a fictionalised ‘Yerzhan,’ who understands his experience of nuclear violence only in terms of the generic tropes of mythology and folklore, including the story of Gesar, a Tengrist myth in which Gesar, Tengri’s son, is sent from the sky to kill the demon Lubsan. Contemplating the event that preceded his disability, his bathing in irradiated water near the Semipalatinsk Polygon, ‘Yerzhan’ concludes,

This story [of Gesar]… was about him, and he had to solve this riddle, which had caught hold of him and wouldn’t let him go.

The Zone! The Zone!, he thought one night, It’s that terrible demon Lubsan! The Zone had taken him captive; the Zone had forced upon him the draught of forgetfulness. And until he reached the Dead Lake – the same Dead Lake in which he had once bathed – he would never be freed from this enchantment. After all, the story said as much: there, by the Dead Lake, Tengri would 15 ‘Ержан понимал, что эта сказка, как и те жыры, что он проигрывал в своей голове, — о нем и что ему следует разгадать эту тайну, которая вцепилась в него, не отпуская…Зона! Зона! — вот страшный демон Лубсан, — думал он другой ночью. Это Зона захватила его в плен. Это она напоила его напитком забвенья. И пока он не достигнет Мертвого озера — того самого озера, в котором он некогда искупался, он никогда не освободится от наваждения. Ведь говорит сказка, что там, у Мертвого озера, Тенгри избавит его от наваждения…’ (Ismailov, Vunderkind Erzhan). It’s also possible that this all-powerful ‘Zone’ represents another kind of generic borrowing, from science fiction; the motif of the ‘Zone’ was the subject of the Strugatsky brothers’ Roadside Picnic, on which the film Stalker (dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979) was based.

In the narrator’s telling, the slow violence of the Soviet bombings becomes almost fantastical, as the narrator’s generic borrowing serves to make Yerzhan’s ‘monotonous’ story more exciting (‘The Zone! The Zone!... It’s that terrible demon, Lubsan’). The mythological frame also endows Yerzhan’s story with a kind of narrative logic: ‘Yerzhan’s’ disability becomes a kind of ‘enchantment,’ from which he can be ‘freed’; the Dead Lake, to which the adult ‘Yerzhan’ returns, expands to possess a kind of symbolic significance beyond the simple, violent fact of its irradiation. Indeed, for the narrator, the Dead Lake – that Soviet invention, which, in Yerzhan’s telling, is so clearly tied to the project of ‘“overtaking”’ the ‘“Americans”’ – ceases to represent anything particularly nuclear at all: as it becomes the stuff of myth, it loses the political reality of its formation.

The narrator continues to rely on the genre of mythology as he attempts to identify a meaning in Yerzhan’s story. Towards the end of the novella, he asks,

Yerzhan sits above me… What did it all mean? Had time, an entire era of it, congealed in him, to suddenly open up in front of me? Did he bind these two worlds of bodies and shadows like a Puer aeternus—an Eternal Child, a divine being, Gesar or Eros, forever tempted by the sky? What is he about, this little man of a great country that 16 ‘Вот он сидит надо мной, 27-летний мальчик, застрявший в своем двенадцатилетнем теле. О чем было это все? Время ли, целая эпоха застыла в нем, чтобы вдруг открыться передо мной? Связал ли он собой два мира — мир тел и мир теней, как Puer aeternus — Вечное Дитя, божественное существо, Гесер или Эрос, которого извечно искушает небо? О чем он — этот маленький человек большой страны, которой уже нет?’ (Ismailov, Vunderkind Erzhan).

The narrator ultimately sees in Yerzhan, most of all, a story: the boy in whom an entire era ‘congeals,’ but who doesn’t represent anything particularly nuclear at all. Insofar as Yerzhan has anything to do with the Soviet Union – ’that great country that no longer exists’ – his image is entirely disconnected from any kind of violence. Instead, Yerzhan is reduced to the abstract idea of an ‘eternal boy,’ ‘Geser or Eros’(Eros, too, is a particularly striking mention here, the Greek eternal cherub having little to do with Yerzhan apart from his age). The narrator, we understand, is looking for a story, hence his central question, ‘o chem on?’: what is Yerzhan about?

The narrator turns to the generic pattern of myth to render Yerzhan’s story understandable and to tell it compellingly, with a kind of recognisable narrative logic. But in the narrator’s interventions to make the story less ‘monotonous,’ the story’s violence disappears entirely; the tragic events of the story are attributed to the unreal and the fantastical, rather than the concrete and the political, as Yerzhan gets subsumed into a larger canon of deities and ‘eternal boys,’ rather than portrayed as a victim of a totalising faith in progress, no matter the cost.

The Island of Shattered Dreams, Tahitian author Chantal Spitz’s generation-spanning 1991 novel about a Mā’ohi family, offers a kind of origin story of both the French bombs and Mā’ohi resistance to them, presenting the French nuclear tests as the extraordinary consequence of the centuries-long pattern of colonial violence and domination in Mā’ohi Nui, beginning with the arrival of missionaries in the eighteenth century. The eventual protagonists, sister and brother Tetiare and Terii, are young adults when French officials establish the Centre d’Expérimentation de Tirs de Missiles Nucléaires, a clear analogue to the Centre d’Expérimentations du Pacifique, the French facility responsible for manufacturing the 193 bombs detonated in the coral atolls of Moruroa and Fangataufa between 1966 and 1996.

As has now been well established, the French bombing of Mā’ohi Nui was unambiguously violent: several of the bombs were knowingly detonated in dangerously close proximity to populated areas, the current inhabitants of which continue to suffer from thyroid cancer at disproportionately high rates. The decades of bombardment also took a toll on the atolls themselves: in 1979, after a below-ground bomb was mistakenly detonated at less than its usual depth, 110 million cubic meters of coral and basalt were sheared off the submarine landmass of Moruroa, causing a nine-foot-tall wave to sweep through a nearby archipelago. But even in 1991, five years before the detonation of the last CEP bomb, and several decades before the unsealing of French government archives, the bombings appear, in The Island of Shattered Dreams, like a kind of apocalypse: the novel, which begins with the creation of the earth,ends shortly after the first bomb is dropped.

But like The Dead Lake, Spitz’s novel is as attentive to the project of its own making as a written work as it is to the devastation of French nuclear violence: by the end of the novel, Tetiare becomes a writer, and articulates an intention to pursue ‘her abandoned dream, of writing the history of her country and her people, their history.’The novel’s last line is an explicit, self-referential nod to itself: turning to his sister, Terii says, ‘“We were born on the island of shattered dreams.”’

In a way, then, the novel self-consciously tells the story of its own creation, paying particular attention both to the ways in which its characters come to understand their lives and their surroundings in this way, as composed of ‘shattered dreams,’ and to the circumstances that produce this writer-protagonist, who is in many ways an avatar for Spitz herself (the dedication makes this more or less explicit: Spitz’s real-life mother and grandmother, to whom the novel is addressed, have the same names as Tetiare’s).

But Spitz’s relationship to the act of writing, like Ismailov’s, is incredibly fraught. Many of Tetiare’s poems, which have titles like ‘Music without lyrics,’ explicitly problematise the political utility of writing, and question its ability to accurately capture any iteration of French violence enacted on Mā’ohi Nui, including the devastation of thebombings. One such poem, Ti’amāra’a (‘Liberty,’) which appears towards the end of the novel, is worthy of particular attention. The poem begins,

J’ai écrit ton nom dans le ciel sans nuage

J’ai crié ton nom dans la vallée sans écho

J’ai chanté ton nom sur la mer sans rivage

J’ai pleuré ton nom dans mon cœur sans rêve.

J’ai effacé ton nom dans ma mémoire sans lendemain

J’ai caché ton nom sous le voile de l’indifférence

J’ai perdu ton nom sous la puissance de l’argent.

J’ai oublié ton nom sous les huées des hommes…

I wrote your name in the cloudless sky

I screamed your name in the echoless valley

I sang your name on the shoreless sea

I cried your name in my dreamless heart.

I erased your name in my tomorrow-less memory

I hid your name under the veil of indifference

I lost your name under the power of money

I forgot your name under the jeers of

17

Spitz, L’île des rêves écrasés, 195-196.

‘Ti’amāra’a,’ at first glance, is striking in its movement from writing (‘I wrote your name…’) to nonverbal expressions of emotion (‘I screamed your name,’ ‘I cried your name’) and, eventually, to absence (‘I hid your name,’ ‘I lost your name,’ ‘I forgot your name’). The poem, then, evinces a distinct lack of faith in the project of writing itself, which it undermines as early as the opening stanzas.

Interestingly, however, this text also represents a kind of literary borrowing, somewhat similar to the kind employed by Ismailov’s narrator in The Dead Lake: ‘Ti’amāra’a’ is very likely a parody of a well-known French poem of the same name, Paul Éluard’s Liberté (1942), itself remarkable for its singular focus on 18 Thank you to Jérémy Bingham for bringing this to my attention!

Sur mes cahiers d’écolier

Sur mon pupitre et les arbres

Sur le sable sur la neige

J’écris ton nom

Sur toutes les pages lues

Sur toutes les pages blanches

Pierre sang papier ou cendre

J’écris ton nom

On my school notebooks

On my desk and the trees

On the sand on the snow

I write your name

On all the read pages

On all the white pages

Stone blood paper or ash

I write your

19

Paul Éluard, “Liberté,” Poésie et vérité (Paris: de la Main à plume, 1942), 26, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k316180j/f13.item#.

The stakes of this kind of borrowing, however, are far less clear than in The Dead Lake. Where the generic borrowing of Ismailov’s narrator effaces nuclear violence, distorting Yerzhan’s life story to encase it in the more innocuous, recognisable genre of myth, Tetiare’s borrowing instead studiously undermines the text borrowed: in Spitz’s novel, the skeleton of Éluard’s poem can appropriately accommodate Tetiare’s subject matter (Mā’ohi independence, the two decades of French nuclear bombs detonated in Mā’ohi Nui) only after its central refrain (“I write your name,” as an affirmative statement of significant power) is refuted. Tetiare’s poem, therefore, not only problematises the act of writing itself, but also rejects the very possibility of a kind of intertextual project like that of Ismailov’s narrative, which would seek to make nuclear violence familiar and shift our gaze from the indigenous people who experience it firsthand.

But despite Tetiare’s own doubts about the possibility of the written word to depict that which defies language, her desire to become a writer herself – and participate in an enterprise that had otherwise ‘remained the domain of outsiders,’ little explored by the Mā’ohi Nui – also reflects a kind of cautious optimism. And though Tetiare appears self-reflexive about her project at various turns, Terii does not: after reading Tetiare’s nearly-finished manuscript, he tells her ‘You must write your 20 Spitz, L’île des rêves écrasés, 200. Emphasis mine.

By the novel’s conclusion, however, the project of writing is once again put into question, as Spitz forces us to wonder what kind of story her novel represents after all. While The Island of Shattered Dreams draws significant attention to Tetiare’s writing, the text that materialises in the novel’s final paragraphs is not Tetiare’s, and, surprisingly, has little to do with the concerns of the Mā’ohi at all. Instead, The Island of Shattered Dreams concludes with Tetiare’s receipt of a diary written by Laura, a white French researcher at the Centre d’Expérimentation de Tirs de Missiles Nucléaires.

For Laura, whose diary is quoted at length in the final third of the novel, the story of French nuclear testing in Mā’ohi Nui is an intensely personal one: the majority of her entries concern her love for Terii, with whom she has a brief, intense relationship. But in describing her feelings for Terii, Laura employs the ecstatic – and, therefore, highly generic – language of a love story. In one of her final entries, she writes, describing Terii,

Il était beau, comme le soleil qui se lève

Ses mots d’amour, comme le chant des sirènes

Effaçaient la triste réalité du monde.

Il était jeune, comme un jour à peine ébauché

Ses sourires, comme l’arc-en-ciel multicolore

Éclairaient mon âme baignée de pluie.

Il était beau, il était jeune,

La folie éternelle de l’amour

A bercé mon cœur de rêves impossibles.

Il était beau, il était jeune

La raison des hommes me laisse orpheline

D’un amour sans lendemain.

He was beautiful, like the rising sun

His words of love, like the sirens’ song

Wiped away the sad reality of the world.

He was young, like a day barely begun

His smiles, like a multicoloured rainbow

Lit up my soul bathed in rain.

He was beautiful, he was young,

The eternal folly of love

Beguiled my heart with impossible dreams.

He was beautiful, he was young

The reason of men leaves me an orphan

Of a love without

21

Spitz, L’Île des rêves écrasés, 187

Laura’s pat expressions of love (‘He was beautiful, like the rising sun’; ‘the eternal folly of love / beguiled my heart’) feel somewhat ancillary to the more urgent concerns of The Island of Shattered Dreams (as well as to its language, which is often deeply original, rooted in extraordinary and estranging descriptions of the earth). But in the universe of the novel, it is precisely the generic, innocuous language of the love story – rather than the specific, intentional poetics of Mā’ohi experience – that survives as part of a textual record: Laura’s diary, the bound book Tetiare holds in her hands and conceals from her brother on the novel’s final page, is the novel’s most tangible textual output, and its only material addition to a kind of written archive.

Laura’s outsize significance in what might have been a kind of Mā’ohi textual record is further underscored in the novel’s final line, from which it derives its title. This line, ‘We were born on the island of shattered dreams,’ is presented not as a kind of transcendent understanding, however pessimistic, reached organically by the two Mā’ohi siblings, but rather as a reference to Laura, the only one Terii makes in the twenty years after her departure: ‘En vingt ans, [Terii] ne fait qu’une légère allusion à Laura:“Nous sommes nés sur l’île des rêves 22 Spitz, L’Île des rêves écrasés, 201. But if the novel’s title is a ‘light allusion to Laura,’ whose story, then, are we reading? Does it matter?

Like The Dead Lake,The Island of Shattered Dreams gradually replaces its own story of slow violence with a more recognisable, palatable one, borrowed from another genre. As a result, its violence also disappears. Not incidentally, The Island of Shattered Dreams, which tells the story of one of the largest-scale, most outrageous inflictions of suffering in human history, is often sold and advertised as 23 (From Amazon: ‘L’Île des rêves écrasés met en scène ce malaise omniprésent qui déchire la Polynésie française d’aujourd’hui. Si son écriture semble agressive, c’est à une histoire d’amour que l’auteur nous convie…’) , a testament, perhaps, to the borrowed genre’s successful cannibalism of the novel’s more unruly, difficult concerns. The slow violence of nuclear testing, both novels seem to suggest, can in fact be made narratively compelling, but only at the cost of the violence itself.

But there is, I think, something more at stake in these two literary texts than the poetics of nuclear literature, and the generic borrowing that can rob the nuclear of its violence: though Spitz and Ismailov are certainly concerned with narrative form, they are also both clearly attentive to who, in the end, gets to tell the stories of nuclear violence. In

The Island of Shattered Dreams, the bombing of Mā’ohi Nui ultimately falls under the narrative purview of a white French woman, whose doomed love story is readily accepted as its emotional core; though the narrator The Dead Lake is of an unspecified ethnicity, his imperfect understanding of Yerzhan’s dialect of Kazakh make him out to be, at the very least, an outsider to the region, who nevertheless appropriates and distorts Yerzhan’s life for the purpose of creating a compelling story.

The generic borrowing in these texts, then, not only erases the violence of the bombings, but also works to wrest narrative control from the people who experienced them in the first place. Both The Dead Lake and The Island of Shattered Dreams are concerned about the kinds of generic borrowing they depict only insofar as they represent the repackaging of indigenous stories by outsiders, for whom the violence of the bombings, as recounted by those affected by them, is either uninteresting or irrelevant. The texts, in other words, reflect specific anxieties about the power structures underlying the production of the written archive: whose stories get listened to? Whose stories get told, and by whom?

For a long time, the story of the French bombing of Mā’ohi Nui was barely told at all, and most French documents relating to it were classified until as recently as 2013. And though the French government has begun to publicly recognise the effects of the bombings, awarding meagre financial compensation to people whose medical problems can be definitively linked to the activities of the CEP, recipients of the awards are disproportionately white, rather than Mā’ohi; many, like Laura, were once workers at 24 Moruroa Files. . Even three decades after the publication of The Island of Shattered Dreams, one can easily note a discrepancy in the kinds of people who are listened to, and whose stories are recognised as possessing a kind of monetary value.

For Kazakh victims of the bombings, the chain of appeal was even less clear: the Soviet Union dissolved shortly after the closure of the Semipalatinsk Polygon, in 1991, and Kazakhstan became independent. But the story of the Polygon – and of the Nevada-Semipalatinsk movement, the transnational coalition that helped closed it – was quickly metabolised into a kind of nationalist myth, used to neatly signpost a triumph against the Soviet state, with little regard for 25 See: Nursultan Nazarbayev, Моя жизнь: от независимости к свободе (Astana: Foliant, 2023), 219-247. Cited in Nari Shelekpayev, ‘Between ‘Streetlight Effect’ and ‘Tunnel Vision’: Perspectives for the Study of Central Asia,’ forthcoming in Kritika. .

As The Dead Lake and The Island of Shattered Dreams help demonstrate, there are material stakes to the storytelling of transnational nuclear violence. Perhaps, the texts seem to suggest, we should adjust our expectations of the kinds of stories we expect, and from whom we expect to hear them.