Do You Think You Can Dance? Mythologies of National Dance in Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan

I started the summer of 2023 with a post in a Tashkent nostalgia Facebook group. Its members – many now living in Israel, Greece, Russia, Germany and the United States – regularly share old photos and facts about their Tashkent, that of their youth. Given that I was writing about the music and dance of that very period, I figured I’d try my luck. ‘I am a PhD student at Harvard writing about the national music and dance of Soviet Uzbekistan,’ I said. ‘If you have any contacts in this sphere, please let me know. I would be very grateful.’ Within several days, dozens of people had written to me and kindly offered their help: a TV journalist had given me the contact information of several Soviet-era dancers, one of whom was over 90 years old; one woman agreed to introduce me to her neighbour, a former dancer in the famed women’s Bahor Ensemble; and yet another gave me access to her personal archive, having herself sung in a popular band for a while. I felt like I had got to know half of Tashkent.

One of the individuals I met through this group was a well-known expert on national history and culture. When we met, she first tested me on my knowledge: could I name the three schools/styles of Uzbek dance? Could I name several famous dancers from each school? Who was the founder of the Bahor Ensemble? After passing, albeit perhaps not with flying colours, we began our conversation. I explained that I was indeed studying Soviet Uzbek national music and dance – but that I was comparing them with their Kazakh counterparts. She was incensed. ‘Uzbeks are a naturally dancing people,’ she fumed, ‘but Kazakhs do not dance at all!’ When I told others the same thing, the response was similar: ‘How can you compare day and night?’ people asked. ‘Uzbeks dance. Kazakhs don’t!’ The vociferousness of their claims startled me—where were they coming from?

While my goal in this essay is not to determine the veracity of such statements, I hope to reveal some insight into their Soviet-era context and history and then discuss their contemporary afterlives. I will largely compare Uzbeks and Kazakhs (one historically largely sedentary group and one nomadic one), but will add Tajiks and Kyrgyz (sedentary and nomadic, respectively) into the discussion as appropriate, given that they were subject to similar dance-related ideas and stereotypes in the Soviet period. My hope is not necessarily to question Uzbek and Kazakh national history but to consider how/when their official versions were shaped, as well as the consequences this bears for contemporary Uzbeks and Kazakhs.

The Soviet project of nationality ensured that recently delineated Central Asian peoples had their own distinct national cultures, including music and dance. Existing traditions – songs, fabrics, movements – were folded into distinct Central Asian national identities. Sometimes, this artificially divided two ethnic groups, such as Tajiks and Uzbeks. Though they traditionally lived ‘deeply interconnected lives, in which customs and practices were identical, bilingualism common, and language never a node of identity,’ they were now to have their own distinct schools of shashmaqom (a genre of classical music native to the city of Bukhara), a tradition that Persian and Turkic-speakers had traditionally 1 Adeeb Khalid, Making Uzbekistan: Nation, Empire, and Revolution in the Early USSR (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 292. But nationality policy also capitalised on obvious distinctions between certain Central Asian people groups. Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Turkmen, and Karakalpaks were nomadic; Tajiks and Uzbeks were sedentary. Some languages were mutually intelligible, some were not, with Tajiki belonging to a different linguistic group than the (Turkic) rest altogether. Some lived in the mountains, others in the steppe. Different lifestyles and histories created a variety of musical and dance traditions, and now they were attached to nationality, a state-sponsored label used to categorise a multiethnic populace.

As the Soviet state associated different nationalities with their respective cultural traditions, it both created certain myths about and attached a particular valence to them. Though all Central Asian peoples were ‘culturally backward,’ Kazakhs seemed to be even more ‘backward’ than their Uzbek neighbours: 2 Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017), 23. Scholars, state officials, and performers regularly claimed that the people’s alleged lack of dance was a ‘tremendous gap [and] insufficient development… in the art of the Kazakh 3 Central State Archives of the Republic of Kazakhstan (hereafter QROMA, as in Kazakh), f. 1242, op. 1, d. 27, l. 64. The same was said of other nomadic peoples, such as Karakalpaks. Elizaveta Petrosova, the foremost Soviet scholar (and alleged ‘creator’) of Karakalpak dance wrote that during her research, she ‘was confronted with unexpected difficulties—the people had no dance; a people with distinctive high culture and a rich [tradition of] applied arts, oral literature, numerous songs and melodies did not dance,’ in effect casting doubt on the existence of the Karakalpak high culture she 4 Elizaveta Artemovna Petrosova, Karakalpakskiĭ tanet︠s︡: metodicheskoe posobie (Tashkent: Izd-vo lit-ry i iskusstva, 1976), 13.

Soviet scholars offered reasons why these nomadic peoples allegedly had no culture of dance, among them ‘the[ir] semi-nomadic lifestyle, few migrations, lack of consistent communication [among] a big group of people bound together by a single birthplace, [and] field of 5 Petrosova, 4. But the rationalising of Kazakhs’ alleged lack of dance came in great contrast to primordialist discussions of each Soviet nationality’s ancient past and great literary figures (such as the philosopher-writer Abai in Kazakhstan or epic hero Manas in 6 Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire, 442. Adherents of the primordialist conceptual framework believe nations and national identity to be fixed and inborn, while adherents of the constructivist framework believe them to be fluid and constructed. Bizarrely, the Soviet state was quite direct when it came to claiming that nomadic nationalities simply did not have dance before the 20th century. In this way, the state seemed to point at nomadic nationalities’ lower levels of development, which, in its eyes, warranted violent campaigns meant to alter their lifestyles, as outlined by scholars like 7 Sarah I. Cameron, The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan (Ithaca [New York]: Cornell University Press, 2018). (Such efforts to “sedentarize” Kazakhs involved requisitioning their flocks – their main source of livelihood – en masse while simultaneously subjecting the population to grain requisitions, causing millions to starve.) Nevertheless, the belief that Kazakhs do not have dance has both persisted and evolved in post-Soviet Kazakh society and Central Asia more broadly, as I demonstrate below.

Uzbeks, on the other hand, were much more commonly associated with dance in the Soviet period. Claims of their culture’s longstanding dance culture and/or inherent disposition toward dance were common. In her book on Bukharan dance, for example, Roziya Karimova writes that ‘the traditional school of Bukharan dance… has preserved the first primitive movements [pervopliasy] and dance pantomimes, imitative dances and simplest dance games, [and] the highest ‘academic’ professional choreography. This rich legacy of dance reflects the uniqueness of the people’s cultural development,’ which, in the case of Uzbeks, had clearly included dance for 8 Rozi︠i︡a Karimova, Bukharskiĭ tane︠t︡s (Tashkent: Izd-vo lit-ry i iskusstva im. Gafura Gul︠i︡ama, 1977), 5. Upon arriving in Uzbekistan in the 1930s, composer Aleksei Kozlov observed that when the two girls in his neighbourhood swept the yard, ‘it wasn’t work for them; rather, it was some kind of spontaneous dance which they did to their own quiet singing. Their suppleness and innate need for movement was amazing… and they weren’t exceptional. Girls that age all 9 Theodore Craig Levin, The Hundred Thousand Fools of God: Musical Travels in Central Asia (and Queens, New York) (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 19. Foreign visitors, like the Chinese-Afro-Caribbean dancer Si-Lan Chen, repeated similar tropes about how Uzbek dance was both beautiful and integral to local society: ‘The pure, untheatricalized Uzbek dance was the most satisfying folk form I had ever seen, rich and gay, spirited and the very essence of spontaneous 10 Si-lan Chen Leyda, Footnote to History (New York: Dance Horizons, 1984), 169–70.

Indeed, it is hardly an exaggeration to say that at least 20-30% of the covers of the Soviet-era cultural journal Sovet O’zbekiston san’ati (literally ‘The Art of Soviet Uzbekistan’) feature either well-known solo dancers or those from the Bahor Ensemble. Uzbek national dancers also frequently grace the pages of newspapers like Vechernii Tashkent (‘Evening Tashkent’) and Qzil O’zbekiston (‘Red Uzbekistan’). Those old enough to have experienced a Soviet childhood often confide to me that they went to dance classes with the hope of being able to gain acceptance to Bahor.

On the 1989 episode of the popular Soviet musical TV show Utrenniaia Pochta (lit. Morning Mail) that took place in Tashkent, for example, national dancers featured in performances by the popular bands Yalla and Sado and the massively popular singers Natalya Nurmuxamedova and Yulduz Usmanova. Given that the show was only thirty minutes long, this is a lot of Uzbek dancing! The Morning Mail episode that took place in Alma-Ata, however, featured a tremendous array of singers—but had only one performance specifically devoted to dance, by the song-and-dance group Gulder, after the final credits. No musical performances were integrated with dance, as they were in Uzbekistan. Kazakh national dancers appeared far less on the pages of republic-level magazines and journals, and national dance ensembles seem to have been less popular there than their counterparts in Uzbekistan. While in Uzbekistan, Tamaraxonim, the founder of Uzbek dance,, has a museum dedicated to her, in Kazakhstan, I have met strikingly few people who have even heard of her Kazakh equivalent, Shara Zhienkulova. It is, of course, possible that Zhienkulova’s name was more widely recognised in the Soviet period, but the fact remains that the legacy of these Soviet-era national dancers is vastly different in these two former republics.

As ethnic pride becomes more widespread in Kazakhstan (along with trendy T-shirts with phrases like ‘Born to Be Qazaq’), so have cool podcasts and Instagram pages for young people about Kazakh history. A post with about 21,200 likes from about a year ago, for example, – proclaims that ‘Kazakhs never danced,’ in effect continuing the Soviet-era belief. The speaker explains that ‘from ancient times, our ancestors have preferred fights [boi] to dances… They preferred to show their strength and agility.’ Whether or not this claim is true, much of the population has seemed to accept it as a badge of honour. As the friend who sent it to me said, ‘I agree with him 100%. Tough times didn’t let us grow our dancing traditions.’

Other arguments that I have seen about Kazakhs’ alleged lack of dance relate to the modesty and piety of traditional Kazakh society. Cultural critic Amina Kurmangaliqyzy has claimed that ‘those who say that the ‘Kara Zhorga’ [dance] is the dance of our ancestors probably do not know Kazakh values, traditions and customs. Women didn’t even look men in the eyes, didn’t cross their path, but here they were all dancing... And shaking their bodies indecently? No one had seen or heard of anything like this.’ In 2023, a local scholar claimed to me that once Kazakhs had converted to Islam, dance went against shariat, and Kazakhs ‘forgot their dance culture.’ While these claims may have elements of truth, neighboring Uzbeks and Tajiks, as we now know them, practised the same religion and held similar, if not the same, values of modesty. I have yet, however, to find someone in these societies who claims that Tajiks or Uzbeks ‘never danced’ for reasons of either religion or modesty (even if, say, women’s dance was performed only for women). It is, of course, possible that nomadic societies had different codes of conduct and value systems that called for different conduct between men and women, but I still find it hard to believe that Islam, say, inhibited the development of dance in nomadic societies but not sedentary ones.

The nationally-conscious young people who proudly note that Kazakhs ‘forgot’ dance because of their piety or did not practice it due to modesty norms might be disappointed to discover that Soviet scholars and public figures regularly made the same proclamations as part of their adherence to the party line. For instance, Sabit Mukanov, the famed Kazakh writer, wrote in 1938 that ‘in the old Kazakh aul [encampment],there was no dance, but the word bi [‘dance’] was preserved... It is evident that dance had long existed among Kazakhs, but was forgotten over the last centuries, just like powder and lipstick had fallen out of use among Kazakh 11 S. Mukanov, Sotsialisticheskaia Alma-Ata, July 4, 1938, as cited in Е. Брусиловский and E. Brusilovskii, Vospominaniia s kommentariiami i illiustratsiiami (Almaty: Tselinny, 2023), 206. Such beliefs became so ingrained in Soviet sources that even foreign scholars studying the USSR repeated them. For example, the American scholar Mary Grace Swift, writing about Soviet dance in 1968, echoes the argument about modesty and gender roles when writing about Kyrgyz dance: ‘dance was once taboo among them. Even simple rhythmic movements in time to music were frowned upon. The appearance of a woman dancer on the stage three decades ago would have been considered sacrilegious by the very same people who were now warmly applauding the popular ballerina 12 Mary Grace Swift, The Art of the Dance in the U.S.S.R (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968), 185. (This is the same person who wrote that ‘Kazakhstan was also one of the regions where no dance tradition existed. The explanation was given that in regions such as this, where the feet would sink into desert sands, the people did not engage in dancing, but all this was changed with the development of Stalinist friendship among the Soviet 13 Swift, 188.

The same ideas – about, say, modesty or religious observance impeding the development of dance – are not common across contemporary Uzbekistan, despite rising rates of Islamic observance that might encourage scholars to examine their nation’s cultural history through a more religiously informed lens. Former president Shavkat Mirziyoyev signed an order in February 2020 ‘On Measures for the Further Development of National Dance,’ cementing the existence (and rebirth) of the Soviet-era Bahor Dance Ensemble, which has now been touring across the world – to the United Kingdom, China, Morocco, Russia and beyond in the past few years, in addition to regular performances at state events in Uzbekistan.

The ensemble’s Soviet-era counterpart even merited its own episode, together with its founder Mukarram Turg’unboyeva, on the 2000s-era Uzbek TV show Zvezdopad (lit. ‘Starfall’). Commonly referred to as the founder of modern Uzbek dance, Tamaraxonim also merited her own episode on the TV show. Popular Soviet-era dancers such as Malika Axmedova have TV specials devoted to them, and professional dancers are frequent guests on all manner of entertainment and talk shows. When I was invited onto a live late-night talk show in Uzbekistan, one of the other guests was a professional dancer—who I was pushed to dance with (live on air!) several times. Interestingly, I was dressed in an Uzbek-inspired two-piece suit and doppa, or headpiece, and the hosts and guests commented frequently that I ‘looked Uzbek.’ I wonder if it was my physical appearance that led them to assume that I would ‘be able to dance,’ just as any member of a ‘dancing people’ would be able to.

Evaluating the claims of Uzbeks or Kazakhs to be ‘dancers’ would require tools beyond those at my disposal and, quite frankly, that I insert myself into too many contentious debates. But as the five Central Asian states build their national identities following the collapse of the USSR, ethnic consciousness has become increasingly ‘cool,’ especially after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. There is absolutely nothing wrong with this. It is, however, worth considering the constructed nature of the designs, slogans, and beliefs that have become so popular. Would, for example, my Kazakh friend – who, after February 2022, has made an effort to speak only Kazakh – be so proud that Kazakhs allegedly ‘never danced’ if he considered the Soviet history of the trope? On the other hand, does it change anything for my Uzbek friends that the Soviet trope of Uzbeks as a ‘dancing nation’ continues to boost their national image?

In a way, the trope of ‘dancing Uzbeks’ and ‘non-dancing Kazakhs’ continues to reflect – and impose – the national hierarchies of the Soviet period. Kazakhs’ nomadism led the state to see them as ‘less developed’—which, among other things, led to its massively violent sedentarisation campaign, killing around one quarter of the population. While Uzbeks were also negatively impacted – with thousands of lives lost – by the state’s concurrent collectivisation and dekulakisation campaigns, the intention was that this would bring them into the fold of Soviet agricultural and industrial development, rather than attack their way of life, which, at the very least (in the eyes of the state), included 14 Dekulakisation was a Soviet campaign of deporting, arresting, and executing allegedly wealthy peasants, known as “kulaks,” in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

But while nomadism has become cool again in Kazakhstan – with Air Astana, Kazakhstan’s national airline, calling its loyalty club ‘Nomad Club’ – dancing hasn’t quite received the same treatment. It’s worth noting that Soviet scholars like Lidiia Sarynova began to push the envelope by 1976. In her work on the history of Kazakh ballet, she wrote that ‘until now… this piece of national art has not yet been touched. It is only known that the [Kazakh] people has dance… which comes from shamanism and religion… One thing is clear: that it is necessary to lead determined academic work on the creation of Kazakh folk 15 Lidiia Petrovna Sarynova, Baletnoe iskusstvo Kazakhstana (Alma-Ata: Nauka, 1976), 36. If Soviet scholars were doing it, then, is it worth reconsidering certain claims? Contemporary Kazakh youth might do well to challenge the Soviet conceptions they have about dance, just as they have debunked those about nomadism. It seems that old beliefs are dying hard—and are potentially denying the Kazakh population access to an area of their culture that they have been quick to dismiss, or whose existence they deny. In a sense, the Kazakh population continues to bear a burden of sorts, that is, the belief that their nomadic way of life deprived them of a socially popular art form.

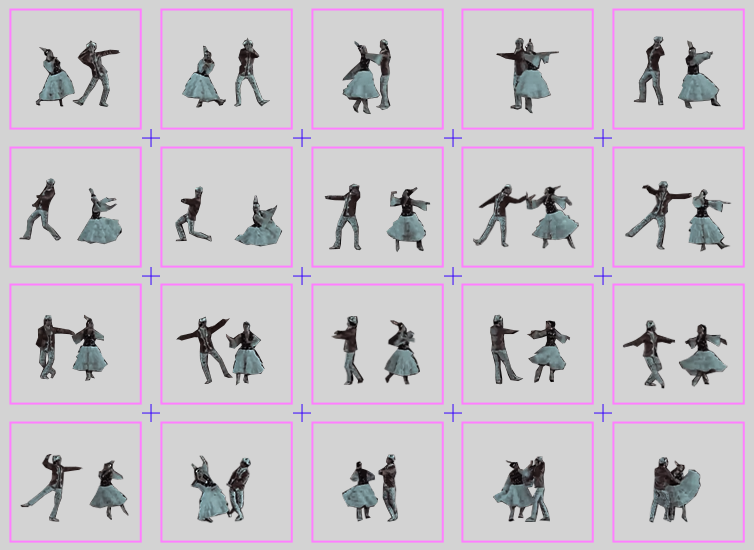

Uzbekistan, on the other hand, continues to benefit from Soviet-era beliefs. T-shirts at popular stores feature images of young dancing Uzbek women, and festivals of Uzbek culture invariably invite professional Uzbek dancers to perform. Would there be a benefit to examining the roots of the image of the ‘dancing Uzbeks?’ Scholars may be interested to look closely, for example, at the non-Uzbek roots of many of Uzbekistan’s first dancers – Tamaraxonim (ethnically Armenian), Isakhar Oqilov (Bukharian Jewish), Galiya Izmaylova (Tatar) – often obscured in both Soviet-era and contemporary histories. None of this is meant to disparage or dismiss the rich heritage of Uzbek dance, but rather, to expand our conception of it and introduce some complexity to the routine of, for example, the Bahor Dance Ensemble.

I’ll admit to catching myself making Soviet-style generalisations as I work on my dissertation. But as a scholar of Soviet Central Asian history, I have an obligation to challenge the assumptions that not only historians but also ‘regular people’ have about history. Most of this knowledge, of course, has little practical value—but perhaps it will bring more meaning into the way we dance.