The Truth of the Collective Farm Museum of the Krasnaya Zarya Cooperative in the Organisation of Avant-Garde Cultural Production

The research was conducted in collaboration with Oksana Kapishnikova as part of the art expedition of the Bishkek School of Contemporary Art (BiShSI) to the Talas region. As a result of the expedition, the zine-catalogue ‘Aralash #5. Talas. Art. Cinema’ was published, created by the co-founders of BiShSI — Sıyınat Joldosheva, Alima Tokmergenova, Oksana Kapishnikova, Diana Ukhina and Bermet Borubaeva, with the assistance of Meder Tovkeev. Some texts from the catalogue were used. (See https://bishci.com/aralash).

The art expedition to the Talas Region, organised by the Bishkek School of Contemporary Art, became a revelation — a kind of initiation reserved for the ‘privileged’ due to their status as free cultural workers. This privilege, tied to symbolic capital, contrasts with the precarity of working without stable income, often driven by pure enthusiasm. Who else would cross two mountain passes just to offer free art workshops for Talas residents, share experiences, and collaborate with local museums without compensation?

The research on cultural sites in the Talas region spans from the early 20th century to the present day. It draws on a variety of sources, including extensive archival materials, publications, interviews, artworks, books and personal observations of the activities of creative organisations in the region.

The significance of this research lies not in nostalgia or claims about the virtues of the Soviet Union. Rather, it offers a detailed examination of cultural questions, collective participation and the construction of an environment centred on human needs — positioned in direct contrast to the neoliberal agenda that shapes contemporary culture. The analysis is grounded in an examination of cultural production – whether through museums or film screenings – and explores economic relationships between private and collective ownership. It considers alternative ways of fulfilling aesthetic and cultural needs through collective self-organisation. The kolkhoz museum and the House of Culture emerge as sculptural forms, not merely buildings or collections of objects, but as imprints of a utopian model of institutional work shaped by collective thought and shared involvement, free from alienation in the process of collective decision-making.

Meta-narratives that generate numerous myths, along with our fragmented perceptions of the so-called ‘truth’ behind socialist projects, now hinder class distinctions and the critical analysis of specific phenomena. This forms the foundation of this publication, which offers tools to magnify and closely examine everything that has happened to us and around us — like viewing history through a magnifying glass.

THE KRASNAYA ZARYA KOLKHOZ MUSEUM AS WORKERS’ SELF-ORGANISATION

In 1959, an exhibition of works by kolkhoz artist Teodor Teodorovich Herzen opened in the Red Corner of the dairy farm at the Krasnaya Zarya collective farm. His paintings, dedicated to everyday labourers – shepherds and tractor drivers – featured portraits of leading kolkhoz workers and landscapes of the surrounding village, rendered in oil and watercolor. This small exhibition marked the first step toward establishing a museum in the village of Orlovka (now Ak-Dobo), originally founded as Johannesberg by German settlers from Poland. The museum actively engaged in educational outreach and continuously enriched its collection with high-quality artworks. A year later, a kolkhoz museum officially opened in the former clubhouse located in the village centre. This event was significant not only for the villagers but also for the residents of the entire Talas Valley. The museum’s inauguration was a grand, festive occasion, drawing a large and enthusiastic crowd.

Thus, in 1962, Teodor Teodorovich Herzen, the accountant of the Krasnaya Zarya kolkhoz, initiated the founding of an art museum with the aim of fostering the ‘aesthetic education of workers and promoting the achievements of Kyrgyz art.’

This promising beginning was supported by establishing close ties with the Kyrgyz State Museum of Fine Arts. Initially, several works by renowned Soviet artists were showcased, followed by travelling exhibitions introducing kolkhoz workers to works by Western European artists from the 15th–19th centuries, contemporary Romanian graphics, and reproductions of paintings held in the State Hermitage, State Russian Museum, and the State Tretyakov Gallery. Several exhibitions of Kyrgyz painting and graphics were also organised. The Ministry of Culture of the Kyrgyz SSR transferred around thirty works by Soviet artists from the Kyrgyz State Museum of Fine Arts to the Krasnaya Zarya kolkhoz. The museum's collection also grew through gifts from artists and acquisitions made by the kolkhoz itself. ‘Over more than twenty years of the museum's existence, over 105,000 people visited it,’ notes Asanbekov in The Kolkhoz Museum [Kolkhoznïy muzey…]. The museum attracted visitors from various regions of the country and Soviet republics, with locals such as kolkhoz workers, teachers, shepherds, housewives and students visiting daily.

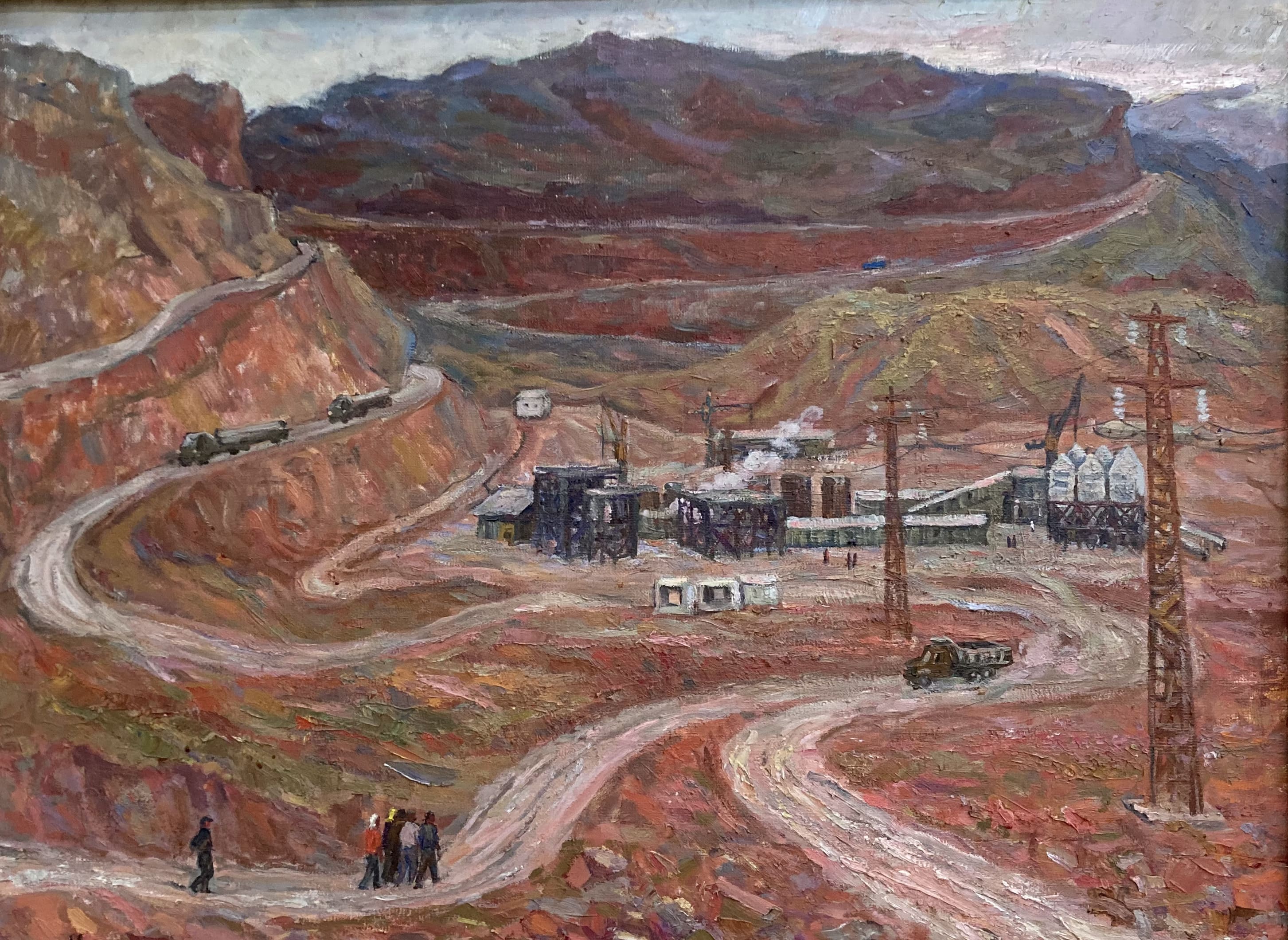

The present-day building of the museum was constructed in 1982. It consists of three halls: the Manas Hall, which also showcases archaeological and local historical exhibits; the hall of works by the Herzen family; and a hall dedicated to famous artists from the Talas region, Kyrgyzstan, and other former Soviet republics. In their work, renowned artists celebrated the labour of the kolkhoz workers from Krasnaya Zarya, representing ethnic Germans, Kyrgyz, Russians, Ukrainians, and other peoples who worked and engaged in cultural activities together.

1: Dilfiruz Ignatieva. Toktogul serpentine. “Krasnaya Zarya” Kolkhoz Museum of Fine Arts named after Herzen, Ak-Dobo village, Talas Region. Photo: Oksana Kapishnikova.

2: Misyurev A. I. Young miners of Kyrgyzstan. 1968, “Krasnaya Zarya” Kolkhoz Museum of Fine Arts named after Herzen, Ak-Dobo village, Talas Region. Photo: Oksana Kapishnikova, 2021.

CHALLENGES OF THE THEODOR HERZEN MUSEUM DEVELOPMENT

The Theodor Herzen Museum of Fine Arts in the village of Ak-Dobo, Talas region, is currently under the jurisdiction of the local Ayil-Okmotu of Ak-Dobo village. However, the museum faces significant financial and resource challenges for preserving and developing its unique collection. Despite the collection of over 1600 artworks, it struggles with exhibition and storage conditions due to a lack of proper infrastructure. The museum is underfunded, poorly known, and often overlooked by the Ministry of Culture’s budget, making it vulnerable to losing valuable artefacts.

Currently, the local government fully supports the museum’s building and staff, which includes the director and the artist. The municipality covers heating and all utility services, such as gardening, cleaning, and repairs. A total of 700,000 KGS ($8,000) per year is allocated for the museum's needs, including its operation and salaries, but this amount does not cover the museum's full needs. There is an urgent need to create a specialised storage facility for the collection according to museum standards, or else valuable exhibits will be lost in the next few years. Currently, works are stored on the floor under the stairs without meeting the necessary temperature and humidity conditions. It is also essential to digitise the museum's records and use modern media to promote it, integrate it into tourist routes, and develop educational programmes.

KRASNAYA ZARYA — LABOUR, CULTURE, HISTORY

The kolkhoz Krasnaya Zarya was renowned as a prosperous ‘millionaire’ collective farm, attracting workers from neighbouring villages. Established in the village of Orlovka (originally Orloff), a German settlement in the remote Talas region, it offered everything necessary for life and development: employment in a livestock complex, a House of Culture, worker housing, and even a fine arts museum initiated by Theodor Herzen — referred to by its founder simply as the Kolkhoz Museum. He personally painted portraits of workers and curated the museum’s collection, selecting the best artworks from across the country. The kolkhoz also boasted a vast library, schools, kindergartens, and even an amusement park with roller coasters and a Ferris wheel — amenities that were not available even in the regional centre, Talas.

Today, the amusement park operates only on special occasions, drawing visitors from neighbouring villages and making it a true celebration for children. However, the park is now littered with trash. The library, once housed in the House of Culture, was relocated to the Herzen Museum after local deputies sold their building and moved into the library’s former space. To save costs, the positions of deputy artistic director of the House of Culture and librarian were eliminated. As a result, there is no longer a creative programme at the House of Culture, and the library now stands idle, with no books being lent out. This cut saves 3,000–4,000 KGS ($34-45) per month—previously the salary of a librarian who managed one of the largest book collections in the Talas region, where children from various places would come to read. Technically, the library still exists, but in reality, its shelves now occupy space in the Herzen Museum, taking over an area once dedicated to storing paintings from the unique collection gathered by Theodor Herzen. As a result, the artworks have been moved under the stairs. It is unclear how these pieces will now be preserved or restored — there is only one professional restorer in the country, and it seems unlikely they will be able to reach this remote location.

By examining the Charter of the Agricultural Artel of the Kolkhoz Krasnaia Zaria of the Orlovsky Village Council in the Talas District of the Kyrgyz SSR, we can gain significant insights. Most importantly, it reveals how the organisation of communal labour fostered a system that addressed the social, cultural, and educational needs of the workers.

It is indeed remarkable that the emphasis on improving quality of life and fostering cultural development is enshrined right in the first paragraph of the Charter. In essence, this becomes the very purpose behind the establishment of the agricultural artel: ‘The working peasants of Orlovka village in the Talas District of the Kyrgyz SSR, having voluntarily united in the agricultural artel Krasnaya Zarya, set their goal and task to manage a collective economy through shared means of production and organised labour. Following the path outlined by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, they aimed to adopt new technologies, utilise scientific advancements and practical experience, increase productivity, and create opportunities for a prosperous and culturally enriched life for both the kolkhoz and its workers.’ (p.1) Of course, the foundation was the existence of state-owned property, with kolkhozes granted a special status regarding land use: ‘All land occupied by the artel, as with all land in the USSR, is state property belonging to the people, assigned by the state for perpetual use — meaning it is permanently allocated to the kolkhoz and cannot be bought, sold, or leased by the artel’ (Ibid).

Nowadays, it’s necessary to rent land or space – often at high costs – to have the right to work, produce goods, or engage in artistic activities. There is no state commission, grants eventually run out, and often there aren’t enough personal funds to cover rent. As a result, instead of opening music schools or book clubs, we see the rise of supermarkets and toykana (banquet halls). The main purchaser of goods and services was the state, which alleviated the kolkhoz from the problem of product sales. They were confident that everything they produced would be bought and focused on production: ‘All activities of the artel are aimed at increasing production and selling the maximum quantity of agricultural products to the state, thereby raising the standard of living of the kolkhoz workers.’ (p.4) According to the charter, a special fund was established to build social and educational infrastructure, as well as leisure, daily life and cultural activities.

GHOST OF THE TALAS HOUSE OF CULTURE

From the Talas House of Culture only a skeleton remains, which, having never been born, was already torn apart brick by brick. Its fate clearly demonstrates the material state of culture, which is reflected in us, in our fates.

The House of Culture was one of the most depressing sights in Talas. Today, it is forgotten and seemingly abandoned. But in the 1980s, a grand project was designed: a hall for almost 500 people, workshops, and even a sports hall. However, as soon as everything was built and furniture and equipment began to be delivered, the entire project collapsed. The unique structure was dismantled brick by brick. Today, all that remains are ruins, serving only as a reminder of the once-ambitious creative vision. In an attempt to preserve it, the House of Culture was once transferred to be a part of a Kazakhstan university, but due to land disputes, the building remains in legal limbo, with ongoing court cases. It seems irreparably lost, as is the possibility of creating a community cultural centre where thousands of children could have learned, practiced music and painting, and received aesthetic education.

I approach the abandoned building. The outside space seems uninhabited, but strange sounds come from within. Homeless people? Thugs? Suspicious thoughts arise, and it feels unsafe inside. Some boys walk by, so I ask them, “Do you know what this is?” They answer that it was supposed to be a school, but it was never finished, and they don't know why. Later, I find out that the people don't even know the building belongs to them — it was once a shared space and has been irreversibly taken. Overcoming my fear, I enter. Strange sounds come from the upper floors: men's voices, as though something is knocking on the floor. I climb to the second floor and see several large circles with stones in the center. A few men are aiming at these stones with other stones. They say they're playing the national game ordo, which means “centre” in Kyrgyz.

It turns out that ordo is a very popular game, with entire teams, including veterans, and regular competitions. The men here are training for such events. This is the centre — where all the pain of this place is concentrated. It could have been a multifunctional cultural centre with sports facilities for various games, including ordo. But instead, all that remains are ruined walls, no music in the classrooms, no painting lessons, no dance rhythms. It feels like seeing the ruins of a more advanced civilisation.

When searching for terms like ‘art,’ ‘culture,’ and ‘Talas,’ news headlines mostly highlight issues such as corruption, money laundering, and mismanagement of local government funds. This content has become more prevalent since the collapse of the Soviet Union. At one point, there were efforts to maintain cooperative farming, but these were undermined by severe legal violations, and eventually, the enterprises were privatised: ‘A number of leaders of agricultural enterprises and labour collectives oppose the development of peasant farms, making collective decisions to withhold land from them. For instance, the village assembly of the Krasnaya Zarya collective farm in the Baikai-Ata district passed resolution No. 2 on April 21, 1993, overturning the decision of the district administration to withdraw part of the collective farm's land for inclusion in the district's special fund and to allocate it to peasant farms.’

At the same time, the enterprises of the agricultural cooperative were completely alienated from the workers themselves: ‘Thus, when the Talas meat plant, milk plant, and Karaburinsky cheese factory were corporatised, the documentation did not provide for the right of agricultural producers to join these joint-stock companies as founders.’ According to new resolutions, they could no longer make any decisions about the organisation, becoming ordinary hired workers who could be dismissed at any moment, seen as mere livestock or unworthy people. They were incapable of managing the enterprise for profit, and had no need for art. The retrospective of the plant's fifty-year history, which we have uncovered, shows us the complete opposite.

Funds for various social projects come, including from the regional development budget, which amounts to 500 million KGS ($5720000) from Djerui. However, the funds often go into the wrong pockets, leaving the initiatives in the hands of determined individuals or groups. Unlike other regions, Talas is less dependent on remittances from migrants, as most of the population works in bean production and other agricultural sectors. Young people tend to move to Bishkek, and attracting new talent to local work is a challenge. Culture-related jobs, like those in museums, pay around 3,000-4,000 KGS per month ($34-45).

One of the most memorable reviews on our festival came from the head of the dance ensemble at the Oganbaev Children's Music School. This is the first ensemble outside of Bishkek in the republic to be awarded the title of ‘Folk Dance Ensemble.’ She said, “I've been working here for 26 years, and I don’t remember anything like this ever being held here.” When Oksana Kapishnikova and I were going through archival documents, we saw how well-organised cultural work was at a systemic level. One document on cinema included the point: ‘showings in every village.’ Would this be even possible now?

Fund No. 208. Archival documents of “Krasnaya Zarya” kolkhoz, Ak-Dobo v., Talas Region. Social Contract of Leninopol cultural department from 1951 on 4 sheets. Talas branch of Government Archive. Cultural Department of the executive community of Leninopol District Council of Deputies of the Workers of the Kyrgyz SSR. Research: Oksana Kapishnikova and Bermet Borubayeva, 2020.

TRUTH. FICTION. MYTH

When planning the art expedition, I only knew that there was a Herzen Museum somewhere in the Talas region, significant in Kyrgyz art history due to his linocut series created for the Manas epic. However, there was no information about the context, history or location. Through conversations with locals, museum visits, the challenges of self-organisation, and archival documents, I discovered a different world. These archival documents acted as a magnifying glass for viewing an era shaped by large socialist construction projects. What appeals to me in Soviet-era projects is the ability to detach from the category of truth and create an imaginative utopia that seems capable of becoming reality.

Each era has its own understanding of truth, a fiction created by imagination or fantasy. Truth is subjective. One can invent a truth for oneself, and it becomes a fiction that is also true. Fiction arises from imagination — more fragments of truth make the fiction appear more fantastic. Yellowed photographs of collective farm life now seem more like fiction than truth. Archival research, grounded in documents from the era, serves as methodological crutches, drawing one truth after another and creating increasingly fantastic fictions. How far can we dig into the truth? If every truth hides fiction, how important is truth?

To the categories of truth and fiction, I would add myth, as we create it from fictions while constructing truth. This forms the basis of implementing policies, establishing and maintaining power. Any power relies on myth – whether the myth of statehood, national development, or the ancient roots of a people – which is fundamental in creating the necessary societal constructs. While fiction may be harmless or even creative, myth has utilitarian significance and can reproduce social phenomena for its own benefit, making it crucial to consider in historical analysis and archival materials.

All archival materials were collected thanks to the staff of the talas regional archive. Special thanks are due to Kadira Koechmanovna Torobekova for her immense contribution to the search for materials related to the cultural documents of Leninpol district, Talas region. her genuine joy in discovering relevant materials on the topic and her willingness to continue collaborating are greatly appreciated.

I would like to express my gratitude to Oksana Kapishnikova for the joint search of materials for the article and to the entire team of BiShSI for the art expedition to Talas and the Talas region.

Sources:

- Asanbekov, S. Kolkhoznïy muzey: Muzey izobrazitel'nïkh iskusstv kolkhoza ‘Krasnaya zarya’ Leninopol'skogo rayona Talasskoy oblasti Kirgizskoy SSR [The Collective Farm Museum: Museum of Fine Arts of the ‘Krasnaya Zarya’ Collective Farm, Leninopol District, Talas Region, Kyrgyz SSR].

- Ishenbekova, N. T. Istoriia zhivotnovodstva Kyrgyzstana (1980–1990 gg.): opyt i problemy [The History of Animal Husbandry in Kyrgyzstan (1980–1990): Experience and Problems]. Frunze: Kyrgyzstan Publishing House, 1984. 120 pp.

- Ishenbekova, N. T. Dissertatsiia na soiskanie uchenoi stepeni kandidata istoricheskikh nauk. Na pravakh rukopisi UDK: 947.1 (575.2) (043.3). Spetsial'nost' 07.00.02 – Otechestvennaia istoriia [Dissertation for the Degree of Candidate of Historical Sciences. Manuscript Rights UDC: 947.1 (575.2) (043.3). Specialty 07.00.02 – National History]. Karakol, 2010. URL: https://libraryiksu.kg/public/assets/upload/works/1140_Ishenbekova_N.T.pdf5e438d60830da.pdf.

- Ustav sel'khozarteli kolkhoza «Krasnaia zaria» za 1964 g. (na 10 listakh) [Charter of the Agricultural Artel of the Kolkhoz "Krasnaia Zaria" for 1964 (10 pages)]. Talas Branch of the State Archive. Fond no. 167. – 10 pp.

- Sots. dogovor Leninopol'skogo otdela kul'tury na 1951 god (na 4 listakh) [Social Contract of the Leninopol' Department of Culture for 1951 (4 pages)]. Department of Culture, Executive Committee of the Leninopol' District Council of Workers' Deputies of the Kyrgyz SSR. Talas Branch of the State Archive. Fond no. 208. – 4 pp.