Recto/Verso: Notes on photographs and archives in Uzbekistan

1. Memory Practices

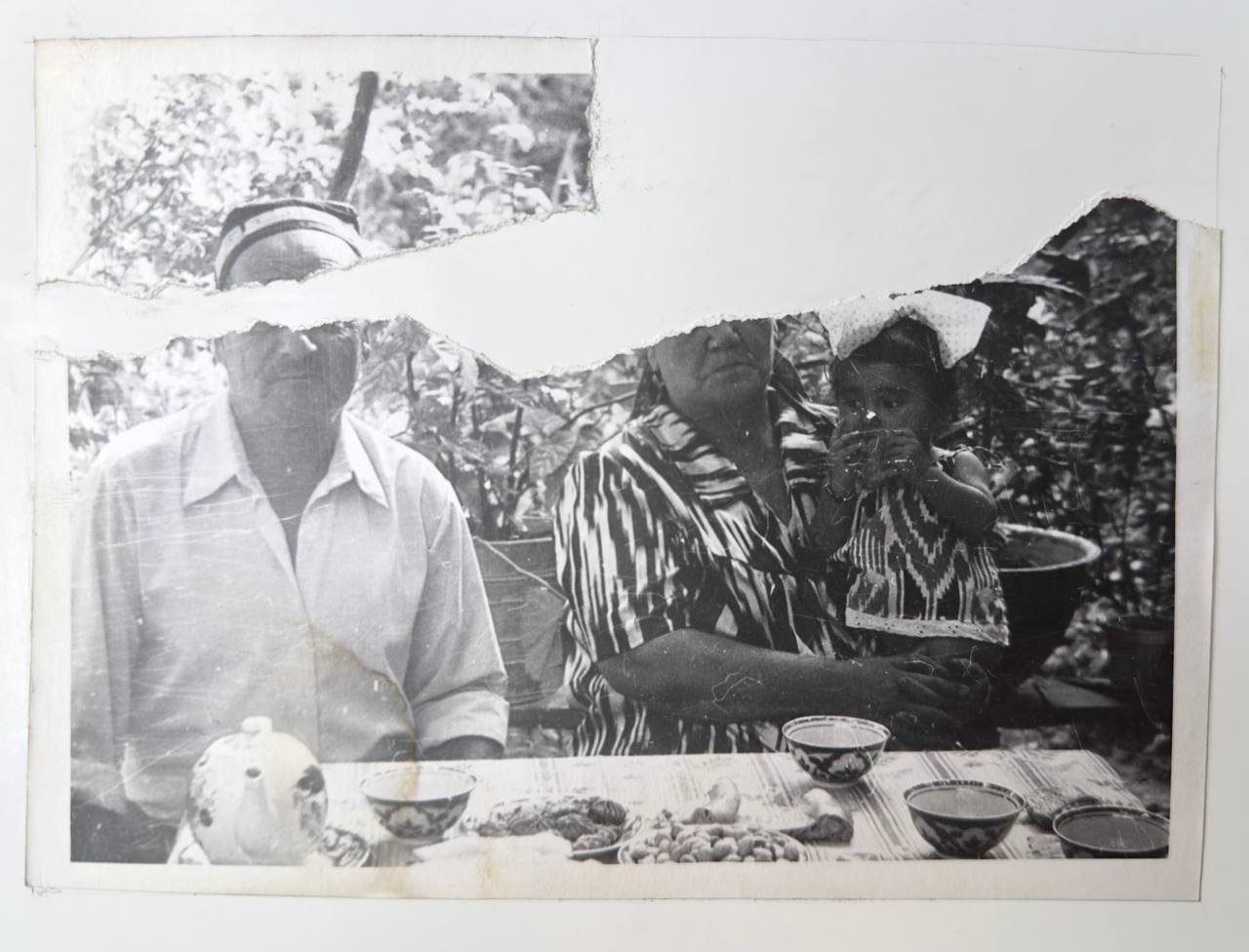

Seated at a table with a teapot, piyolas, fruit and bread, with light-dappled greenery behind them, a man and woman face the camera. But this intimate glimpse of a relaxing family gathering has been disrupted by a brutal tear stretching across the photograph at eye level, obscuring their identities and rendering their faces only partially visible. The gesture calls to mind the censored faces of victims of the purges, whose likenesses were effaced because they could incriminate anyone found with them in their

1

For an overview of Soviet censorship and defacement, see David King, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin's Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1997) and for a recent exhibition with Uzbek examples of censored photographs from the 1930s drawn from Oleg Karpov’s Turkestan Archive, see «Зияющие пустоты», 139 Documentary Center (opened March 30, 2024).

. The young girl resting comfortably in the woman’s arms has been spared this treatment. She nibbles on her piece of bread, unaware of the defacement that has occurred just above the polka-dotted bow in her hair.

This work is drawn from Vyacheslav Akhunov’s series V Pamiat [‘For Memory’], which explores stiranie pamiati, or the erasure of memory . Akhunov links the project with the repeated destruction of memory in service of ideological narratives—cycles he has observed for decades:

"My first thoughts about the erasure of memory appeared in the sixties, when monuments, portraits, photographs and various images of Stalin began to disappear in the city where I lived. Then I encountered the erasure of memory/images in family archives, including ours, when some faces were scraped off to whiteness. My entire conscious life from the early fifties to the present day has passed under the rumble, crackle and noise of ‘the erasure of memory’ from Stalinism through the disappearance of the USSR and 2 Vyacheslav Akhunov, in conversation with the author, August 20, 2024.

The original photograph belonged to a friend of his, a dressmaker, who was getting rid of her family photographs and agreed to let Akhunov keep them. The project relates to the partial loss of his family archive: on an evacuation train during the Second World War, thieves stole his mother’s suitcase, which contained her photo albums. By collecting and reworking other people’s family photographs, he makes a belated and displaced attempt at salvaging his own lost archive.

The title for the series comes from another found photograph, a portrait of three friends, with a swirling inscription beneath it: 3 Akhunov, in conversation with the author, January 24, 2024. For Akhunov, the title invokes a chain of associations, the most important one being the Russian phrase ‘v stol’, which means ‘for the table’, an expression usually rendered in English as ‘for the desk drawer’, used to describe unofficial work made during the Soviet period and tucked away to avoid denunciation, without any hope of being 4 Sometimes rendered in English as “for the drawer”, to convey its being stored out of sight. . From the censorship of potentially incriminating photographs to the production of works without an audience – both gestures prompted by the fear of an official gaze – the works are caught in a circuit of anticipated condemnations and withholdings.

Akhunov also thinks of the solitary nature of working ‘for the drawer’ – for memory – as related to the notion of working ‘for the archive’. In this sense, the archive represents a moratorium, but by setting works aside for an unknown future when the conditions for their reception materialise, it also becomes a space of hope.

Working with this archive of found photographs collected from friends and acquaintances, he faces a void of memory: 5 Akhunov in conversation with the author, August 20, 2024. Unable to relate to the specific content of these memories, he explores the forms their empty shells take.

Much of Akhunov’s oeuvre has been concerned with the mechanisms of ideology and its visual patterns, repeated over and over until their meaning is evacuated. His practice replicates forms of censorship which historically contributed to the loss of memory. But his purpose is not to reiterate the violence of censorship; instead, he observes:iterate the violence of censorship; on the contrary, as he observes:

"I try not to erase the image of a person, but to fragment it by tearing the photograph into pieces, as if the owner of the photograph constantly carried it with him in the pocket of his suit and this caused erasures, cracks and breaks to appear on the 6 Akhunov, in conversation with the author, August 22, 2024.

Beyond defacement, by suggesting the wear and tear that comes from a photograph being cherished, the dislocations of Akhunov’s collages weave redemption into their destruction. Bent over his worktable, he takes care to hold the fragments together so that we look more closely at the scene. The gaps focus our sight.

2. Getting Closer

Video: Gulnoza Irgasheva, ‘There is no one in the attic,’ 2024. Fragment.

The cursor lingers as an unseen user explores a selection of Soviet-era photographs. She zooms in—first quickly, then slowly. Scrolling, roaming, lingering. The photos are stacked in a column, like a strip of Google image search results. Four depict public spaces, while the other nine focus on Central Asian women. The files hover and glow on a laptop screen.

The unseen computer user continues her inspection. As she enlarges the file, the face of a statue of Lenin in front of the Bolo Hovuz mosque in Bukhara dissolves into a grid of increasingly large square grey pixels. She zooms out and moves on to another image, repeating the exercise. This time, she pauses over the shoulder of a woman checking rows of mechanised spindles in an enormous Tashkent textile plant; an opportunity to appreciate the delicate ringlet of hair that stretches onto her cheek.

The next stop on this excursion explores the field of Ben Day dots, part of the printing process, used to reproduce a colour print of three women clipped from a magazine. Instead of letting the dots disintegrate like pixelated Lenin, the user stops once she has cropped the photograph to focus on the thoughtful features of the women on the left. This operation reframes the original photograph and locates a new meaning within it, replacing the impersonal tone with a moment of interiority. The crop introduces a caesura.

Watermarks in the lower right-hand corner indicate that some of these photographs were downloaded from maxpenson.com, while others are stamped with the Open Central Asian Photo Archives, an online platform where digitised photographs are made available to the public from a variety of private

7

This website no longer exists; at present, the website bearing the most complete information regarding the legacy of Max Penson is www.maxpenson.uz. For the Open Central Asian Photo Archives, see https://ca-photoarchives.net. That project is led by Svetlana Gorshenina and Boris Chukhovich.

. Given their different sources and chronologies, the original photographic prints would never have been laid out on a tabletop side-to-side like this. But the uploaded jpegs of their scans face no such limitations, able to float freely and form new (subjective) associations as soon as they were made available for downloading.

This perceptive staging of the experience of looking closely at digitised photographs is drawn from a recent film by the Uzbek artist Gulnoza Irgasheva, There is no one in the attic, 2024. Framed within the film’s yearning to understand the past, the segment is accompanied by a voiceover of the artist’s mother describing the survival of Muslim practices in the Soviet period. The point of departure for the film is Irgasheva’s desire to understand the coexistence of her parents’ seemingly incompatible belief systems (her father was a dedicated Communist and KGB servant). At various points in the film, trying to visualise anecdotes her mother describes – for example, children being forced to drink water at school during Ramadan to break their fast – we watch as Irgasheva types commands for AI-generated images to fill archival gaps.

For me, the mechanism of zooming into the photographs raises questions about how personal memory intersects with official narratives. How should we look at photographs? What is it that they document — and what do they omit or are unable to tell us?

Beyond these questions of content are others related to form and structure, implied by the self-reflexivity of filming the experience of looking: What happens when archival photographs are viewed on computer screens, and how do high-resolution scans expand the possibilities of interpreting photographs? Moreover, can decolonial methods productively scramble the structuring logic of the archive?

3. Delayed Work

It is no coincidence that most of the photographs Irgasheva selects depict women. Some of these are clearly posed propaganda photographs: a woman engrossed in reading the collected works of Lenin, a female worker in a textile factory, girls in uniforms participating in a parade. These are tempered by portraits that inject a more personal tone: a colour photograph of two friends posing in front of a fountain and a solemn black-and-white studio portrait of three women.

Repeatedly cast in leading roles in Soviet propaganda, Central Asian women were photographed to embody ideas, beaming and radiant; to demonstrate, via their bodies, the achievements of Soviet emancipatory policies. Behind the searching curiosity of the user who zooms in until the photographs begin to fall apart, or until they feel more intimate, is a search for evidence of the coercion and violence that accompanied the enactment of these Soviet policies. Where do traces of those narratives reside? Is there room for a redemptive tenderness in the way we look – closely – at such photographs? Can they be reframed within a critical framework that does not take their rhetoric at face value?

In a recent monograph about Soviet vernacular photographs and memory, Oksana Sarkisova and Olga Shevchenko highlight how the reception of photographs is continually re-evaluated according to the imperatives of the present:

"Such is the delayed work of photography: at a historical remove photographs manifest new meanings to inquiring eyes, their ‘answers’ depending on the questions posed, and on the point in time when the image is encountered. Even the most personal photographs exist in the context of the political culture of the moment, which infuses them with meaning, casts some images and events into sharp relief, and temporarily relegates others to the 8 Oksana Sarkisova and Olga Shevchenko, In Visible Presence: Soviet Afterlives in Family Photos (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2023), xi.

The diachronic construction of photographic meaning applies to propaganda photographs as well. These may continue to proclaim their message in the continuous present-tense of photography, but viewers today demand critical readings to dismantle the rhetorical systems that produced

9

This is also apparent in the ways that archival photographs are increasingly featuring in the work of contemporary artists: for example, see the recent “Taming Waters and Women in Soviet Central Asia” research project and installation by Saodat Ismailova and the Davra collective. https://davra.ca/creating/taming-waters-and-women-in-soviet-central-asia

.

When photographs exit the exclusive residency of a physical archive, with its limited access and parameters of control, and begin to circulate online in high resolution scans, the possibilities of developing new approaches to them increase dramatically. Free access enables users to form their own collections, creating new constellations of works according to their own subjective criteria or interests. Of course, photographs can also be instrumentalised in a neo-colonial direction, instead of a decolonial one. Svetlana Gorshenina has addressed the complex politics of nostalgia and post-Soviet nationalisms on memory politics in the active circulation and discussion of photographs on Facebook 10 Gorshenina, “Ethnographic types” in the photographs of Turkestan: Orientalism, nationalisms and the functioning of historical memory on Facebook pages (2017–2019) in Photographing Central Asia: From the Periphery of the Russian Empire to Global Presence (Berlin/Bostson: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, 2022) . But in the ability to scrutinise, to zoom in, to enlarge far beyond their original size or format – to possess the archival photograph and to do with it what you wish – lies the possibility for a contemporary viewer to reconfigure its meaning, to use it as a tool to make sense of colonial history; even, perhaps, to restore agency.

4. Unanswerable Questions

![Unidentified photographer, Self-Portrait, undated. Turkestan Archive [774_036]](/storage/blocks/GmSNDXKXZB5VRgfBwJ01QeHqerDGol9baThZpcSN.jpg)

In a perfect archive, for the recto of each photograph – its frontside, the printed contents documenting a sliver of the world – there would be a faithfully annotated verso, revealed when flipped over. The ideal verso anticipates the many questions that the recto might prompt by offering identifying information: the photographer, the date, the place, the subject, and so on. But of course, the world is messy, there are no perfect archives, and the versos of many photographic prints are blank, or may only have a word or two scribbled in haste. Although we undertake research in search of answers, along the way we often accumulate a longer list of unanswerable questions, which point out the fictions of archival infallibility.

With no caption inscribed on its verso, no information about its protagonist, and no context within which to place it, the only way we can approach this photograph is to look closely. A small print with rich sepia tones, it transports the viewer into a domestic space, where a young man in a white shirt has taken a seat in front of a mirror. His face – youthful, with a hint of a moustache lining his upper lip, his gaze somehow both tentative and assured – peers out from behind the body of his tripod-mounted camera.

Who is this young man? Where is he? How did he acquire his camera? What else did he photograph?

One avenue for contextualising this photograph is to scrutinise the domestic interior for clues about this man’s identity in order to place him within a social history: to imagine the details of his life based on the evidence we have of his material existence. A quick inventory of this space suggests social privilege: the dark wooden furniture, the printed tablecloth draped over the table, the floral prints hanging on the wall. The framed group photograph and the stack of books on the table imply that he might be a student.

Was the photograph made before or after the revolution? The photograph is not clear enough to determine with certainty the model of his camera, but this general type of folding camera was widespread in the 1910s and 1920s. Given the devastation wrought on the generation of young Uzbek intellectuals during the purges of the 1930s, it is difficult not to speculate about what happened to this young man, and to his photographs.

A bowl of cherries on the table: the photograph was probably taken in summer. This information may seem far less urgent or useful compared to all the unanswered questions, but it is an excellent example of the arbitrariness of photographic data, so indiscriminate in its documentation.

Another approach is simply to linger on the significance of the self-portrait. The young man has placed his camera on a tripod and pulled one of the bentwood chairs from the table behind him close to the mirror. By aligning his face with his instrument, he joins an international cohort of modernist photographers who pictured themselves in this way, including Germaine Krull in a famous self-portrait from 1925.

While some self-portraits seek to extract the individual from their environment, this photographer chose to inscribe his presence within a specific locale, even if that specificity is lost to us today. His decision to include the carved wooden frame of the mirror in his composition magnifies the photograph’s self-reflexivity by providing an elegant frame-within-the-frame. The self-portrait indicates a desire to document oneself for posterity. The gesture appears to have been taken seriously: with its rounded corners and fingerprints along the bottom, the physical print appears to have been tucked away and treasured for some time until it was acquired (probably at Yangiabad) by Oleg Karpov for the Turkestan Archive.

A confession: the fact that I am unable to situate this photograph feels like a failure. What is the point of research if it cannot reconstruct the historical narratives this photograph fits into? But research also serves to bring into focus the historical conditions under which archives and narratives are formed. It also delivers us into the presence of material objects which have survived the passage of time. Even by itself, the photograph is remarkable; even (especially?) without the fuller picture of the lost world it depicts—for its survival, for its vividness, for its haunting and poignant documentation of a person’s sense of self.

Verso:

A void. A gap. Also, an invitation.

Recto: A statement:

“Look at me, meeting the world with my camera, marking a day in my life as I make something of myself.”

5. “Without Captions They Have No Meaning”

When the Central Republican State Archive of Film, Photo and Audio Documents was established in the Uzbek SSR in the early 1940s, under the oversight of the NKVD (the secret police), the collection was formed by gathering material from various institutions. As part of the organisation of these disparate collections, an expert commission produced a series of ‘selection lists’ [otborochnye spiski], documents that detail photographs purged from the archive, sent to be recycled [v makulaturu]. These lists deploy bureaucratic language that transforms the gesture of destruction, seemingly antithetical to an archive’s mission of preservation, into a rational decision.

For instance, an inventory dated 6 June 1944 opens with a terse explanation that the expert commission ‘selected for recycling the following archival photo documents of Tekstilstroy, which had lost all historical, defence, scientific and practical significance’, before listing the sizes, contents, and justification for ninety-two photographs that were deemed unnecessary and purged from the archive:

‘General views of the construction and equipment’ were dismissed as ‘duplicates’, ‘superfluous’; ‘technically unsuitable’ [negodnye], ‘broken’;

‘Group shots and portraits’ were not needed because they were ‘vague/uncertain [neopredelennye]’;

A set of photographs described simply as ‘Miscellaneous (children, views)’ were purged because they ‘do not present 11 Ф. Р-2668, оп. 1, ед. хр. 4, л. 3.

Another list from June 25, 1944, includes the perfunctory annotation

12

«без аннотаций не имеют знач., брак: 94» Ibid, л. 5.

On the one hand (recto): erasure.

On the other hand (verso): the impulse to document this destruction, the archivist’s logic of inventory that allows us a glimpse of what was lost. A shadow archive.

6. Double Vision

![Nurmuhamedov, Young Photographers, A Photo-Etude, Samarkand, 1955. Uzbekistan National Archive of Film, Photo, and Audio Documents, Tashkent [0-59367]](/storage/blocks/T3c1qAjHuif2ULkiKsp6Gz2a8kMEm1hB6vTrn330.jpg)

A photograph is a selection. To hold the camera up to the world invites a particular kind of scrutiny and observation: to frame something ongoing and to anticipate its removal.

You can see this split vision on the face of the boy holding the camera. His eyes are fixed intensely on whatever it is he is photographing, invisible to us since it is located beyond the frame of this photograph. The concentration of his gaze and his stiff posture suggest that he is still learning to look at the world through a camera. He seems enthralled. His friend points and doubles back to direct his gaze at the camera. The boys, who look to be about nine years old, are dressed in school uniforms with pioneer scarves. Their bodies are close together, nestled against the trunk of a tree for support.

All that I know about this photograph comes from the index card that inventories its negative, preserved in the State Film, Photo, and Audio Archive in Tashkent. The facts fit into a single sentence: the photograph, titled ‘Young Photographers, a Photo-Etude,’ was taken by a photographer named Nurmuhamedov in Samarkand in 1955. I have no further information about Nurmuhamedov—it is not a name I have encountered elsewhere in the archive, in newspapers and magazines, or on exhibition lists.

But even if the author’s identity does not provide a way into the photograph, the title does. The term ‘photo-étude’ [foto-etiud] comes up again and again in twentieth-century Soviet photographic practice, especially among amateurs. With its French origin (meaning ‘study’) and musical connotations, the foto-etiud invokes a slightly expressive or aesthetic orientation, as if to set it apart from a document.

7. A Photograph of Nothing

![Photo-Étude / Foto-Etiud. Spread from the Album of the House of Pioneers of the Tamdy Region [no. 3203] Bukhara State Museum-Preserve, Collection of Archives and Documents.](/storage/blocks/mGyUc1TDKdTyuzoyI9J6AHSxQ4DzJmdpqgZQoawy.jpg)

Most of this photograph is difficult to see, out of focus and overexposed. Amid the blurred forms and blown-out highlights, a craggy line in the rock leads the eye down towards a dense cluster of ferns. The milky haze is offset by a greater amount of detail in the rock’s surface in the upper right quadrant, which is daubed with warm brown hues that suggest the print may have been improperly fixed.

Although the print does not exhibit any characteristics that signal proficiency, it is labelled with a serious title, proudly inscribed on the page below: ‘photo-étude’. It has been pasted into an album compiled by the photo circle of the House of Pioneers of Tamdy, a district in the Navoiy region north of Bukhara. An album opens with a general view of the regional centre of Tamdy before giving the reader a tour of the city highlights, with stops at the new building of the House of Soviets, a newly built shopping centre, the house of culture, middle school no. 1, and a World War Two monument. Immediately preceding the photo-étude are group photos of members of the photo circle on an excursion to Aktau mountain.

Of all the photo-études I have seen, this is without question my favourite. Aiming the camera down at the ground beneath their feet, a group of children learning to see the world with a camera selected this patch of the ground for preservation. The blurry arrangement of rocks and ferns forms a poignant record of collective experience.

8. Recto/Verso

Collages made of torn family photographs, someone zooming in and out of photographs, an unidentified self-portrait about which nothing is or can be known, two boys learning to use the camera, a blurry photograph of the ground. What do these fragments add up to?

My hope is that these difficult objects might reveal in their silences an inventory of possibilities; that they might help sketch a terrain for thinking about decolonial approaches to the work of memory in independent Uzbekistan; that they might exemplify the tender beauty of the material lives of photographs in the digital age.