Biographies: Yerbossyn Meldibekov

Since the advent of modernity, we have come to perceive time as exclusively linear. Consequently, biographies of individuals and chronologies of events are written from the perspective of continuous development and progress — everything begins with birth and concludes with recent events, where the final point is always death. Furthermore, in the words of Benedict Anderson, we conceptualise time as ‘homogeneous and 1 Benedict Aderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, Verso Books, 1983 Its emptiness and homogeneity suggest that time can be infinitely filled, enabling it to harmoniously encompass not only the fates of many unrelated and unfamiliar individuals but also the lives of successive political regimes, ideologies, and, inevitably, technologies.

This text does not provide an alternative approach to understanding time. In exploring the biography and creative path of Yerbossyn Meldibekov, one of the most significant contemporary artists from Central Asia, it also adheres to a linear narrative. However, it seems necessary to acknowledge that this conceptual framework contradicts Meldibekov’s own logic and perspective. The multimedia artist asserts – a claim central to his practice – that time in his native region is, in fact, nonlinear. From his Kazakhstani viewpoint, time moves along a spiral-like trajectory, with each new cycle returning to a point it has previously reached. Central Asia, therefore, appears destined to relive the same scenario over and over again.

In 2024, the year this note is written, Yerbossyn Meldibekov celebrates his 60th birthday. Born in 1964 into a large family at the Tülkibas railway station in what was then the Kazakh SSR, Meldibekov grew up in the southern region of the country. His father, a railway worker, passed away in 1980, shortly after Meldibekov enrolled in the Gogol Art School in Almaty (now the Tansykbayev College of Decorative and Applied Arts). One of the artist's intriguing memories involves the fact that the village near Tülkibas station was home to many Germans, who had their own specially-established educational institutions. As for Meldibekov, he attended a boarding school for the children of railway workers.

In 1984, after graduating from art school, Yerbossyn Meldibekov began his service in the Soviet Army. This two-year chapter in his life played a surprisingly significant role in shaping his artistic sensitivity and set a particular direction for his multidisciplinary practice. Partly, this was because his advanced artistic skills, honed during his studies in Almaty, often led him to draw maps of regional countries, including, as dictated by the political context of the late USSR, Afghanistan. Up to the present, says Meldibekov, the information he accessed during his military service has informed the development of his projects. This experience also shaped his perception of the region as inseparable from Afghanistan, a country he often refers to as the epicentre of the Central Asian condition (e.g., The Seasons of the Hindu Kush, 2009 – 2011).

In 1987, after completing his service in the Soviet Army, Yerbossyn Meldibekov enrolled in the Almaty Theater and Art Institute, initially in the Applied Arts department. However, realising his strong aversion to the then-dominant visual system obsessed with national ornamentation – a style he had already encountered as a student at art school – he decided to transfer to the Sculpture department. This decision would prove pivotal for his career.

Reflecting on his ambitions as a student, Meldibekov openly shares that after graduating, he dreamed of sculpting stone portraits of communist leaders. He grew up observing how members of the Artists' Union, endorsed by Soviet authorities and whose careers thrived on ideologically-driven commissions from the Communist Party, lived comfortably and lacked for nothing. Meldibekov, too, hoped for such a stable existence after completing his studies. However, the unexpected dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, which triggered a profound shift in values across the region and beyond, shattered the artist’s hopes forever.

Nevertheless, it would be incorrect to view those years of sculptural training as wasted, as they provided Yerbossyn Meldibekov with invaluable skills. He learned to work with stone and metal, developed a habit of thinking spatially, compositionally, and plastically, and, perhaps most importantly, gained like-minded peers during his university years. One such significant figure, who greatly influenced Meldibekov’s aesthetic, was Kanat Ibragimov, whom he met at the institute. Recalling these times, Meldibekov notes that Ibragimov stood out for his broad cultural knowledge and intellectual curiosity. He was deeply interested in contemporary artistic practices, passionate about music, and engaged with culture in its many forms. Meldibekov’s first clearly articulated artistic projects are closely linked to Ibragimov’s influence. In 1994, two years after their graduation, the two artists joined forces to establish the Kökserek collective, which later evolved into a gallery.

The name chosen by Meldibekov and Ibragimov for their collective speaks volumes about their artistic positioning in the early 1990s. The name Kökserek may be familiar to Kazakh audiences from the eponymous story by writer Mukhtar Auezov, which tells the tale of a wolf cub taken in and raised by a Kazakh boy named Qurmash. In Russian translation, Kökserek is rendered as ‘Grey Fierce.’ Despite being nurtured in a domestic environment, the wolf retains its wild instincts, and the story ends with Kökserek fatally attacking Qurmash. Young and audacious, Meldibekov and Ibragimov saw a reflection of themselves in the wolf cub, whose untamed nature, despite years of Soviet ‘domestication,’ eventually broke free.

The Kökserek actions truly shocked an unprepared public with their outrageousness and radicalism. Drawing inspiration from Viennese Actionism and the Slovenian collective NSK, the artists created genuinely provocative and experimental art. In this regard, it is important to highlight the work by the collective titled Neue Kasachische Kunst (Action with a Ram), which was presented in 1997 at the Art Moscow Contemporary Art Fair. In front of the audience, Yerbossyn Meldibekov and Kanat Ibragimov slaughtered a ram and then poured its hot blood into bowls, drinking it. Driven by maximal cynicism, the artists specifically invited members of the Moscow Society for the Protection of Animals to the performance.

In the following years, continuing his work individually, Meldibekov maintained his love for performance art, as evidenced not only by his personal projects from the late 1990s (such as Asian Prisoner and Pol Pot, both from 1998) but also by those created in the new millennium.

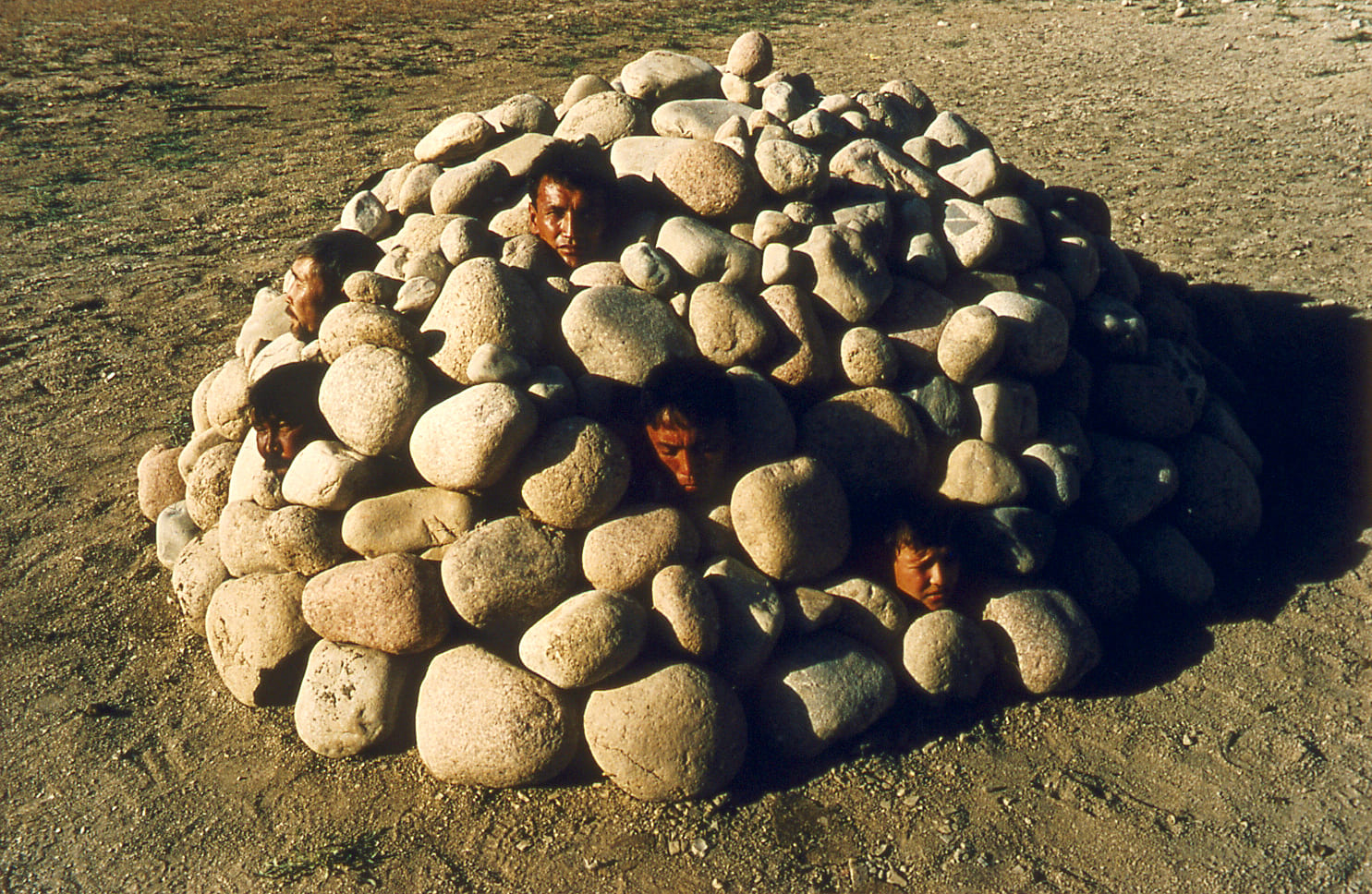

The artist's work in the early 2000s is associated with the emergence of a male character named Pastan. According to the artist's concept, Pastan embodies a collective image of the average Central Asian inhabitant – submissive, cowardly, and passive – losing composure and dignity in the face of those in power.

Through a series of video works, we can observe how Pastan, portrayed by Meldibekov himself – whose Central Asian origins are deliberately emphasised by the taqiyya on his head – silently and selflessly endures unjust and prolonged beatings and insults (Pastan I, 2001, and Pastan on the Street, 2003). We see him laugh in a way that borders on madness (Shu-Chu, 2007), explode in a sneeze (Allergy, 2009), or violently spit in everyone's and everything's face (Spit, 2014). Always silent, these video performances unmistakably and vividly illustrate the various facets of existence for a subject from Central Asia.

"One has to always work with the local context," the artist often repeats. One of the main sources of inspiration for Yerbossyn Meldibekov's work is the history of the region. Formed during the Soviet period, when historical science was an instrument in the hands of ideology, he developed an early interest in alternative histories. This interest, combined with critical thinking, led to Meldibekov's sceptical reception of Kazakhstan's nation-building project following its independence. Against the hegemony of official narratives, he has consistently opposed his own artistic counter-narratives.

One vivid example of this opposition is the work Monument to the Unknown Batyr, or Gattamelata in the Skin of Genghis Khan (1998). This monument, consisting of taxidermied horse legs and hooves, seemingly severed from the rest of the animal’s body and crowned with emptiness, eloquently comments on the phenomenon of the widespread marking of urban public spaces in Kazakhstan's independence era with monuments to various batyrs (brave warriors, honorary title in Turkic and Mongolian cultures). At a certain point, the artist suggests, it becomes irrelevant who the new national-historical iconography demands to honour.

Yerbossyn Meldibekov's practice demonstrates that any monument is performative (Family Album, 2006 – 2011; Transformer, 2013). It is not a static object permanently fixed in the city's space but a dynamic marker that signifies and exposes power relations, which are subject to constant negotiation. The monument changes and mutates over time; it is dismantled, reconsidered, and supplemented. The time of a monument, like the time of people, is linear, which means that, as with people, we can trace its life from its emergence to its disappearance.

Earlier, the artist referenced events that encompassed the entire Central Asian region or at least several of its republics. However, with the arrival of the 2020s, Meldibekov has almost entirely dedicated himself to the internal context of Kazakhstan. This is understandable, as the previous decade, marked by the unexpected resignation of the first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, ended in a dramatic fashion. In the four years of the current decade, the country has undergone significant upheavals, in particular the unrest of January 2022 and the consolidation of power by the new president of the ‘New Kazakhstan,’ Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. These circumstances, in a certain sense, have liberated the artist, allowing him to openly engage with the ambiguous visual legacy of Nazarbayev's authoritarian regime.

In his installation Five Versions of the Author's Fall (2024), Yerbossyn Meldibekov revisits the well-known episode of the demolition of the Nazarbayev monument by protesters in the city of Taldykorgan in January 2022. The fall, which, according to the artist's assessment, lasted three seconds, was a gesture that overshadowed the significance of three decades of the first president's rule. These three seconds symbolically annulled thirty years. The Nazarbayev monument was subjected to a public execution, and his time was interrupted.

Nevertheless, in the context of Yerbossyn Meldibekov's solo exhibition, curated by his long-time collaborator Dastan Kozhamet, the various monuments to the dictator that make up the installation Five Versions of the Author’s Fall (2024) were arranged in such a way that Nazarbayev appeared to rise rather than fall. The upward movement of his body, this resurrection of a political corpse before the public's eyes, disrupting the linear flow of time, created discomfort, suggesting that the process of dismantling the regime is not a thing of the past, but something that Kazakhstanis still have to face.